Culture

Bloody Creek National Historic Site

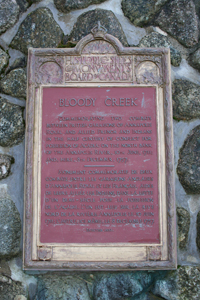

In 1932, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada erected a plaque to mark the national historic significance of two military encounters in the Bloody Creek area. The plaque reads:

Commemorating two combats between British garrisons of Annapolis Royal and allied French and Indians in the half century of conflict for possession of Acadia: on the north bank of the Annapolis River, 10th June, 1711; and here, 8th December, 1757.

10 June 1711

The first incident occurred on 10 June 1711 (21 June on today’s calendar) during a period of tension between the garrison stationed at the fort in Annapolis Royal (formerly Port-Royal), Nova Scotia, and the Acadians of the surrounding area. Eight months earlier, in October of 1710, British and New England forces had captured the fort and, with it, Port-Royal, the capital of Acadia. A temporary garrison of 450 men, consisting of British and New England troops, had been left at the fort for the winter.

Relations between the British administrators and garrison occupying the fort and the Acadians living along the Annapolis River had been tense during the winter of 1710-1711. Great Britain and France were still at war in the War of the Spanish Succession. Only a three-mile radius around the fort had been surrendered with the fort, leaving the Acadians outside the designated area in an ambiguous position. There existed the real possibility that the French might regain the fort, either by attack or by peace treaty; Britain had returned the fort to France at the conclusion of previous wars.

To discourage Acadians from assisting the British garrison, Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, governor-general of New France, had appointed Bernard-Anselme d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, as leader of First Nations and French forces in Acadia and given him added authority by making him an officer in the compagnies franches, the troops which served in France’s colonies. Although young, Saint-Castin was an experienced and respected leader of the Abenakis in what is now Maine and very familiar with the former Port-Royal area. Saint-Castin and Aboriginal fighters, primarily Abenakis and Maliceets, spent the winter of 1710-1711 in the Annapolis Royal area, harassing the fort and threatening Acadians who cooperated with the British.

The provision of building materials to repair the fortifications became a major issue. By the spring of 1711, the fort was in bad condition, with large breaches in the ramparts. Alexander Forbes, the fort engineer, requested Acadians along the river to provide 2000 poles and 400 beams for filling the breaches and revetting the fort walls. Some Acadians cooperated while others did not, especially Acadians on the upper river. Acadians found themselves in a difficult position, caught between the demands from the fort and threats of retaliation from Aboriginal fighters and excommunication from the Catholic Church. Aboriginal fighters, and possibly some of the more recalcitrant Acadians, cut the rafts of timber before they could reach the fort. The supply of timber and lumber dwindled. After fort officials sent troops to meet with Acadians on the upper river, supply resumed but then slowed again. Officials decided to send another detachment.

On 10 June (21 June NS), Captain David Pidgeon led a 70-man detachment up the river with Forbes (the engineer) and about 20 volunteers, including Captain John Bartlet, leader of the previous detachment, and the Fort Major. The detachment was intended as a show of force to demonstrate to the Acadians’ harassers that the British were forcing them to supply timber. Pidgeon’s orders were to threaten the Acadian suppliers and to kill some fowl, if necessary, but to pay compensation.

The expedition made its way up the river in a whaleboat and two flatboats. As the whaleboat carrying the engineer, fort major and others reached a narrow bend in the upper river, Aboriginals fighters attacked. All but one man were killed. The men in the other two boats were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The wounded were ransomed while the prisoners began a trek, to Quebec.

The attackers had consisted primarily of about 40 Abenakis and their leader Simhouret, all recently arrived Pentagouet (now Castine, Maine) and put in place by Saint-Castin. The British believed that there had been 150 fighters. Some of the wounded claimed that a few French men, painted to look like Aboriginal fighters, had also taken part. No Acadians were known to have taken part.

Father Antoine Gaulin, missionary to the Abenakis, presented an alarming interpretation of the situation. He claimed that the British detachment had planned to attack Mi=kmaq families on the upper river, to remove the principal French inhabitants and to burn the settlements on the upper river. The perceived threat by Pidgeon’s men and their defeat mobilized Acadian resistance to the British and New Englanders at the fort, resulting in several weeks of increased tensions, which passed without major incident.

8 December 1757

The second combat commemorated in the plaque at Bloody Creek occurred on 8 December 1757 during another period of tension between Acadians and the administrators and garrison at the fort in Annapolis Royal. In 1755, the government of Nova Scotia had deported the Acadians of Annapolis Royal and other major centres of Acadian settlement. Acadian men who had eluded deportation formed a guerilla force which kept the garrison at the fort closely confined, unable to venture out of town without a covering party. This was particularly the case after the 43rd, a British regiment unfamiliar with Nova Scotia, began to garrison the fort in October 1757.

The battle at Bloody Creek on 8 December was precipitated by an attack, two days earlier, on a party sent out from the fort, across the Annapolis River, to cut firewood. A small force of “Frenchmen” killed a grenadier and took several men prisoner, including John Eason, the master carpenter at the fort. A detachment sent out to rescue the men returned empty-handed. Adding insult to injury, the attackers returned and taunted the fort by a firing their muskets in a victorious feu de jeu. A larger detachment was then organized and set out the same evening.

The detachment consisted of two captains, two lieutenants, two ensigns, four sergeants, two drummers and 100 rank and file, supported by approximately 20 volunteers from the fort and town and led by local men, including John Dyson, the Ordnance Storekeeper. John Knox, a lieutenant in the 43rd , gave a first-hand account in his journal. The goal of the detachment was to recover the prisoners and “to give a sensible check to the rabble for their insolence.”

The British force made its way along the south side of the Annapolis River, searching for a place to cross to the other side, where the Acadians and the prisoners were. After two nights and one day of exposure to the cold, wet December weather, and three unsuccessful attempts to ford the river, the detachment began the trek back to the fort. At eleven o’clock, on the morning of 8 December, as the British crossed a narrow, plank bridge over the René Forest River (now Bloody Creek), the French attacked, killing the commanding officer. After some confusion and cries of “retreat,” the last of the men fought their way across the bridge, to face more fire from a make-shift battery on the other side. The attackers then fled, pursued briefly by the soldiers. Afraid that they would be attacked again further ahead, the British hurried back to Annapolis Royal, leaving most of the dead and wounded behind. Knox reported that the losses amounted to Captain Peter Pigou (the commander of the detachment), a sergeant and 22 soldiers.

Seven months later, in July 1758, some of the prisoners from the firewood party, who had escaped from their captors, arrived at Fort Cumberland, on the Isthmus of Chignecto. A letter from an officer at the fort provided details of the attacks, as told by the prisoners. They stated that the attackers of 6 December numbered about 15 while those of 8 December numbered about 56. The latter consisted of a party that was in the area in search of cattle and provisions. After ambushing the detachment, which greatly outnumbered them, the “enemy” had continued to fight, encouraged by the frightened cries of “retreat.” According to the prisoners, seven of the attackers had been killed and nine wounded. The officer claimed that none of the wounded left behind by the British had been brought back as prisoners, so apparently had been killed. William Johnson (Guillaume Jeanson), whose father had been in the British garrison at Annapolis Royal and whose mother was Acadian, was said to have been the leader of the attackers.

Learn More: Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada

Related links

- Date modified :