Caribou recovery at Parks Canada: out of sight—but not out of mind

It's wintertime in Torngat Mountains National Park in Labrador. The Torngat Wildlife, Plants, and Fisheries Secretariat work with Parks Canada and other partners to prepare for a 35-day remote survey of the Torngat Mountains Caribou herd. By the end of the field season, the crew will have surveyed many caribou over 145 hours across 16,000 km.

The winter population survey of the Torngat Mountains Caribou in Labrador

Select image to enlarge

A lot of collaboration—and resources—are needed to study these largely at-risk animals. Recovering caribou in Canada remains a priority for Parks Canada, both inside and outside of park borders.

Photo: Meredith Purcell

Where the caribou roam

There is one place that people can often see caribou… on the Canadian 25¢ coin! But in nature, the iconic caribou are rarely seen. They prefer undisturbed, colder habitats.

View larger image

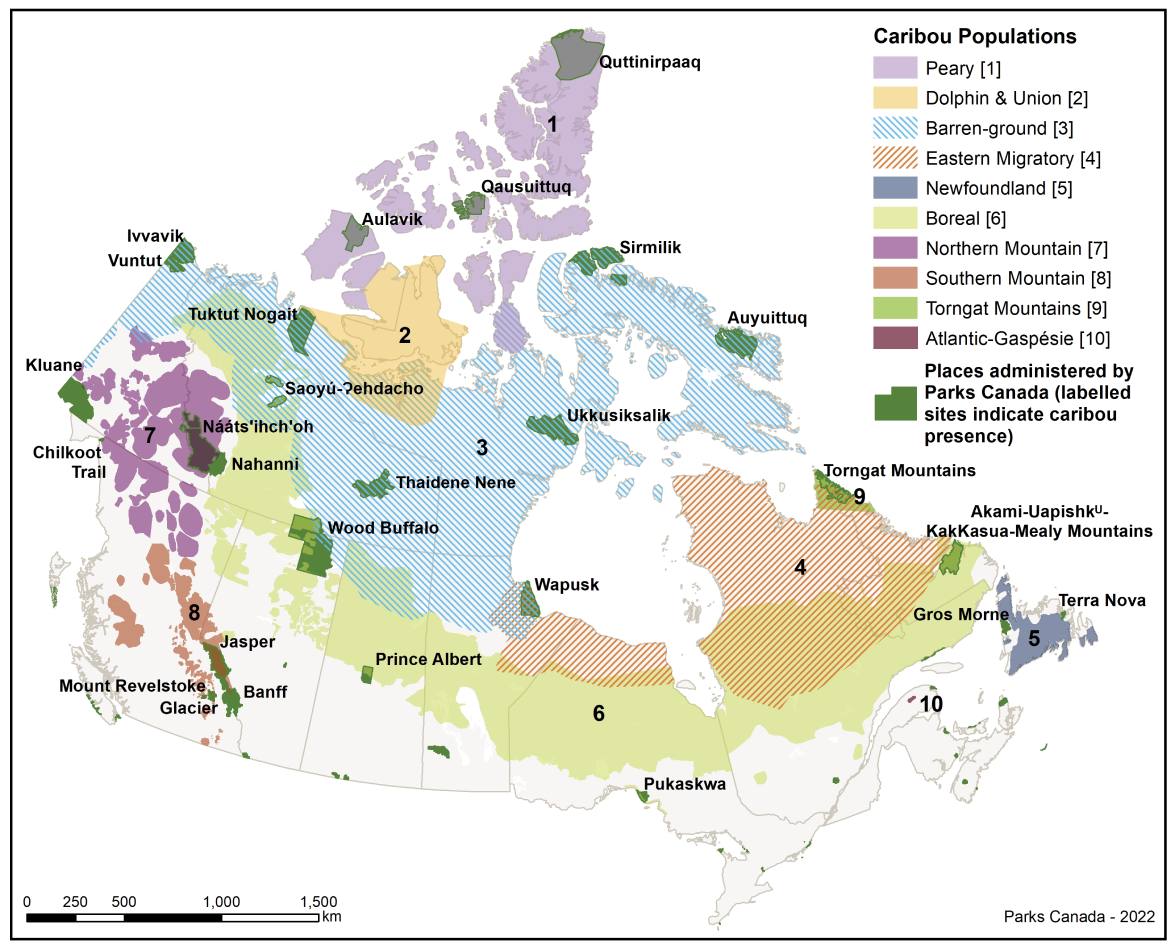

A map showing the habitat range of caribou populations across Canada, along with places administered by Parks Canada. Labeled sites indicate those with caribou presence.

Map description

Each caribou population is numbered from 1 to 10 with a unique colour representing the area of that caribou’s habitat range. Dolphin & Union [2] and Barren-ground [3] caribou populations are Barren-ground caribou, while the Eastern Migratory [4], Newfoundland [5], Boreal [6], Northern Mountain [7], Southern Mountain [8], Torngat Mountains [9], and Atlantic-Gaspésie [10] are Woodland Caribou.

Three different caribou populations in Canada can be grouped by their habitat use and migration patterns:

Woodland Caribou choose habitats where they can avoid predators. In most of Canada, they live in mature and old-growth forests. They can also be found in mountainous areas.

Barren-ground Caribou live in arctic tundra environments. Some migrate long distances in large herds to their breeding grounds—they find protection in numbers.

Peary Caribou are the most northern population of caribou in North America. They are only found in the Northwest Territories (NWT) and Nunavut. They travel in small groups across sea ice and the Arctic tundra.

Threats to caribou in Canada

While caribou live in some of Canada’s most remote locations, they still face risks that threaten their very survival. Some of these include:

- habitat loss: roads and pipelines remove mature forests that caribou need. Predators have easier access into caribou habitat. Forestry and fires transform mature forests into young forests that moose and elk prefer.

- altered predator-prey dynamics: more prey species like moose and elk mean more wolves. More wolves mean greater risk of caribou predation.

- human disturbance and predator access: winter trail users, like skiers, snowshoers and snowmobilers, can push caribou off their favoured habitats. They can create packed trails that lead predators to caribou habitat. Caribou can also be disturbed by dogs and aircrafts, or be killed by cars on roads.

- small populations: some populations do not have enough females to sustain their population. Small herds are especially vulnerable to predators, disease, and accidents like avalanches.

- climate change: warming temperatures can alter snow and ice levels, making it hard for caribou to find important winter food. Climate change is causing more insect outbreaks and wildfires, leading to disturbance and habitat loss.

Parks Canada collaborates with others to address these threats through conservation actions. These include local Indigenous knowledge holders, other governments, and stakeholders.

Recovery in action

Caribou don't recognize boundaries like provinces, territories, conservation sites, and even countries. The lands administered by Parks Canada make up only a small part of caribou habitat. That’s why Parks Canada collaborates with many groups to protect and recover caribou.

Watch this video from Gros Morne National Park and see the work they’re doing to protect caribou by connecting landscapes:

Text transcript

[Tom] Hi, welcome to Gros Morne National Park.My name is Tom Knight.

I'm a biologist here with Parks Canada.

We’ve got a beautiful, calm morning here

in Gros Morne National Park...

…heading into the park to do the caribou habitat work.

So you can see the beautiful landscape

part of Gros Morne National Park in the Lowlands.

We can also see in that landscape

there's some power lines and roads and the community.

And so if you're a caribou, these are all things

that are a part of your landscape.

This project looks at the cumulative impacts

of all of this sort of development,

including climate change

and other things that happen on the landscape,

like forestry and agriculture.

How do those impact

caribou movement through the landscape?

So the Newfoundland Caribou is actually considered

its own kind of unique population genetically

and in their behavior and whatnot.

They are listed as special concern

under the Species at Risk Act,

which means that

they're not near extinction or anything,

but that we should be keeping a close eye on them

and planning for things like future habitat.

You can actually see there's

quite a few tracks, some caribou and moose.

Gros Morne National Park and

all national parks in general,

really provide a core habitat.

In the summertime,

they move into the hills where they have their calves.

But these lowlands are really important,

in winter time especially,

when they come and they can crater down through the snow,

and find nutrition and the vegetation they need to survive the winter.

So a big part of our project

is trying to protect caribou by predicting

where they will potentially cross roads

and show up on highways.

And we can do things like install these signs behind me.

The more motorists are aware of these issues,

the safer that they can be

and the safer it is for the caribou.

We're just getting set up here with all the gear.

We can take a look here and see

what Doug and Rory are up to…

[Doug and Rory] Hello!

[Doug] So what we're trying to do is

get a good understanding of

what type of habitats caribou are using.

So part of that work

is moving on the ground and collecting

information on land cover types.

We're just getting the drone prepped now for our flight.

This camera captures imagery

the same as you'd get from a high-altitude satellite.

This will allow us to characterize

the habitat that the caribou are using.

The camera, which Rory has, captures two types of imagery:

one is regular picture,

but it also captures thermal imagery,

which we hope to use to detect animal locations.

[Tom] So if you passed over a caribou,

then it would actually show up as a thermal image?

[Doug] Yeah, that's what we're testing.

[Tom] All right, so we’ve got Rory ready

to take off with the drone here...

And she's lifting off.

[Rory] You can see the drone flying in a grid pattern

over the study area.

[Tom] Okay. So what are we looking at now, Rory?

That's interesting.

[Rory] So here we're looking down from the drone

and we're seeing the caribou habitat.

There's a nice mosaic of lichen

and different types of mosses.

Lichen is one of their main dietary resources.

[Tom] So that noise we're hearing is that

taking pictures or…

[Rory] That's the shutter, yes.

[Tom] Okay.

[Rory] And you can even see here on the side

there's the caribou paths.

It's rewarding seeing those trails.

It means we're in the right spot.

[Tom] Yeah. Yeah, for sure.

And really, a lot of the theme of this project,

the idea of connectivity and

caribou being able to move through a landscape safely

from one place to another...

So just coming out into the bog here,

while the drone is doing its thing.

Nous allons jeter un œil à certaines des plantes,

Just do a close up look.

The lichens, the white lichens you see there,

they're favorites of caribou during the winter.

And you can see it's a mix of sedges, mosses, lots of beautiful colors.

Sphagnum moss often turns this bright red.

[Rory] It's beeping us and telling us that the drone is.

[Tom] Okay.

[Rory] finished the flight and it's on its way

back to the landing point.

[Tom] So we had a couple of successful flights today.

This is something that's going to actually help map

the caribou habitat across the entire province,

across the whole island of Newfoundland.

Yeah, sure.

So what we'll do with that information

is take it back to the lab and that'll help

paint the picture of what type of habitat

caribou are using in this area.

Breeding a new generation of caribou

Parks Canada is undertaking an innovative caribou conservation breeding program. This program is the first of its kind for caribou in Canada. It aims to rebuild small caribou herds in Jasper National Park in Alberta. Parks Canada is working with others on this, including:

- Indigenous peoples

- provincial governments

- non-governmental organizations

- academics

- and other experts

Watch a video about the changes in predator-prey relationships and small populations of caribou in Jasper. Watch another video about the caribou breeding program at Jasper National Park.

Text transcript

Caribou in Jasper National Park are in danger and need our help.The Tonquin herd has fewer than 55 caribou and only about 9 breeding females.

The Brazeau herd has fewer than 15 caribou and only 3 breeding females.

The Maligne herd was declared locally extinct in 2020.

The root of the problem is complex, but can be linked to early park management practices.

In the early 1900s, wolf control programs kept wolf numbers very low.

Without many wolves, elk populations soared.

Then in 1959, wolf control practices ended abruptly.

With an abundance of elk for food, wolf population numbers quickly recovered and increased.

Wolves began competing among themselves for resources in the main valley.

They started travelling into less accessible caribou habitat more often.

Naturally, they preyed on caribou they came across.

As a result, caribou populations declined sharply until 2016.

Since the 1970s, the elk and wolf populations have steadily declined to more sustainable numbers.

Which means that today, the conditions are much better for caribou to thrive.

However, caribou populations are now too small to recover on their own.

If we don’t act now, the Tonquin and Brazeau herds will disappear.

The best option to rebuild these herds is to establish a caribou conservation breeding program.

Learn more about the caribou conservation breeding project in Part 2: Caribou Comeback.

parkscanada.gc.ca/caribou-jasper

Like. Comment. Share.

pc.gc.ca/parksinsider

Parks Canada

Canada

Text transcript

Caribou in Jasper National Park are in danger and need our help.Since 2006, Parks Canada has taken actions to mitigate most threats through:

restoring and encouraging a natural wolf and elk population balance,

limiting the impacts of humans on caribou-wolf interactions,

and protecting critical caribou habitat.

These steps have created better conditions for caribou survival and recovery.

But these actions were not enough to overcome the high wolf populations of the past.

Caribou populations are now so small they cannot recover on their own.

The best option to rebuild these herds is to establish a caribou conservation breeding program.

Through conservation breeding, Parks Canada would:

capture a small number of wild caribou,

breed them in a protected facility,

release the caribou born in the facility into their natural ranges.

Based on what is learned, Parks Canada will adapt the project along the way.

But before we decide whether to move forward, we need to hear from you.

To be successful, we need to learn from Indigenous partners, stakeholders, and the public.

Have your say in the future of caribou in Jasper National Park.

To learn more, visit parkscanada.gc.ca/caribou-jasper

Like. Comment. Share.

pc.gc.ca/parksinsider

Parks Canada

Canada

Research and monitoring

The Western Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else in Canada. A big question we have is how climate change will affect caribou. Parks Canada and partners are working together to understand how climate change will impact caribou populations in Ivvavik National Park. Data from this study, combined with Indigenous Knowledge, will help us predict these changes so we can better protect caribou. Watch the video below to find out how.

Field Notes: Predicting habitat changes for Porcupine Caribou

Text transcript

[Parks Canada beaver logo]A Parks Canada employee sits in front of a helicopter, collecting plants from the ground.

[Name Tag] Laurence Carter, Ecologist, Ivvavik National Park

[Laurence speaks directly into the camera while standing in an Arctic tundra landscape.]

Hi, everyone.

My name is Laurence and I'm the ecologist

in the Western Arctic Field Unit with Parks Canada.

[Location Tag] Ivvavik National Park, Yukon North Slope

And we're here in the gorgeous North Slope just by Sleepy Mountain.

[Laurence turns the camera to show Sleepy Mountain behind her.]

We're doing our first sampling site.

[A hand picks cotton grass flowers to place in a plastic bag of vegetation samples.]

So today we're sampling vegetation.

[Title] Field Notes, Predicting Habitat Changes for Porcupine Caribou, Ivvavik National Park

[Text] Climate change is affecting the Porcupine Caribou herd. Warming temperatures mean more biting insects, unpredictable weather, and changes to the plants that the herd eats.

[Text] Parks Canada is one of many government and Indigenous groups collaborating to study these changes across the herd’s core range, which extends far beyond Parks Canada borders.

[Laurence retrieves sampling tools from a helicopter.]

So what are we collecting here?

[Name Tag] Colleen Arnison, Resource Conservation Manager, Ivvavik National Park

[Colleen speaks into the camera while standing in front of the helicopter that brought the group to the research location.]

So right now we're going to go onto the ground and collect some cotton grass heads.

They look like this.

[Text] Cottongrass is one of the caribou’s favourite spring foods!

[Parks Canada employees crouch on the ground, collecting plant samples and placing them in plastic bags for later analysis.]

[Text] Warming temperatures can reduce the amount of nutrients available in plants. We’re collecting samples to analyze their nutritional value.

All right, Colleen, you're talking the big talk.

Show us your technique for picking cotton grass flowers.

[Colleen bends down to demonstrate the technique she uses to pluck cotton grass flowers from the ground for sampling.]

Yeah, so it's to pull and use my knuckles and to grab a bunch at the same time.

That's amazing, very impressive.

[A caribou walks along a shoreline, foraging for food.]

[Colleen speaks into the camera.]

The heard as a whole when they come together on the Yukon North Slope and on the Alaskan North Slope...

..the last estimate was done a few years ago and it was over 220,000 animals.

[Images of caribou from the Porcupine Caribou herd flash across the screen.]

Caribou are so important to people in the local area.

They're important culturally.

They're also really important for the ecosystem

by, like, moving nutrients around because they move such large areas

[A young caribou chews a cotton grass flower.]

where they're picking up different plants and then pooping them in different areas,

so they're actually, like, creating, like, a nutrient cycle with the way that they move.

They also, like, shape the landscape.

So in areas, like, along the mountains, you'll be able to see,

[Caribou runs in a straight line across the landscape in Ivvavik National Park.]

like, their line drives because they've been in this area for thousands of years.

They've been walking the same routes, which is just incredible.

[Text] If the caribou can’t get the plant nutrients they need, they could eventually leave their core range to forage elsewhere.

[Text] Data from this study, combined with Indigenous Knowledge, will help us predict these changes so we can better prepare for them.

[Laurence speaks directly into the camera. She crouches down and plucks a horsetail from the ground and shows it to the camera.]

We’re at our first site this morning, another gorgeous day to be outside.

And today we've come across a species we didn't see at all yesterday, it’s horsetail.

It’s all these tiny sprouts you see coming from the ground.

Now, this is still, like, very… we're still, like, very early in the summer.

[Colleen is laying on the ground to get a closer look at the horsetail.]

Are these the horsetail?

There are so many of them. Oh, my gosh.

Welcome to the world, little guys! [Laughter]

[Name Tag] Kaitlin Wilson, Program Manager, Wildlife Management Advisor Council (North Slope)

[The researchers laugh together while sitting on the ground collecting vegetation samples.]

Look at them all!

[Small blue flowers appear on the screen. The camera turns to Colleen, who is standing nearby.]

Colleen, what are those flowers called?

[Colleen speaks to Laurence, who is standing behind the camera.]

These ones there that you just took a photo of?

They’re anemones.

Wow. Can you say that three times fast?

Naname, naname, naname.

Ananamane, ananamane, ananamane...

Anemone! [bell dings]

We have a winner! [Laughter]

[The small group of scientists sit on the ground in a circle, collecting vegetation samples. The group packs up their equipment and loads it into the helicopter.]

[Laurence speaks to the camera as she sits in one of the collecting sites.]

So temperatures

[The camera flies over Ivvavik National Park, displaying a rugged, rocky landscape and then a greener landscape with an alpine lake.]

in the Western Arctic are warming faster than anywhere else in Canada.

[Photos of caribou flash across the screen.]

And a big question we have is how climate change will affect caribou.

And one of the ways is through plants and vegetation.

So climate change and increasing temperatures

has led to a lot more shrubs popping up in the Arctic

[Scientists are collecting vegetation in various locations in Ivvavik National Park and showing the samples to the camera.]

And it can also lead to a different timing of when plants green up.

So plants can become green maybe, like, earlier in the year than they normally do.

And so we're really curious to find out how that's affecting Caribou.

So, a lot of the work we're doing here will help us know

[Text] Parks Canada and partners are working together to understand how climate change will impact caribou populations, so we can better protect them in the future.

[Text] Parks Canada is proud to collaborate on this project with: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (LEAD), United States Geological Survey, Department of Environment | Yukon Government, Wildlife Management Advisory Council (North Slope), Polar Continental Shelf Project | Natural Resources Canada.

[Text] Parks Canada places can help caribou and other species adapt in a changing climate. Find out how: parks.canada.ca/climate

End screen directing viewers to related videos.

Parks Canada logo

Canada wordmark

Staff at Vuntut National Park are also looking at the effects of climate change on caribou habitat. Parks Canada researches and monitors caribou with many partners at Nahanni National Park Reserve. Staff are using DNA from scat to learn how caribou herds are connected.

.jpg)

Parks Canada also conducts aerial surveys to count caribou at Pukaskwa National Park in Ontario. Caribou are monitored at Jasper in Alberta and at Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks in British Columbia using:

- aerial surveys

- remote cameras

- radio collars

- and scat analysis at Jasper

Reducing harm to caribou

Parks Canada is working to reduce harm to caribou in many ways. We’re making roads safer for caribou—and drivers—at Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland.

Area and trail closures at Jasper, Glacier, and Mount Revelstoke National Park help protect Mountain Caribou from disturbance and predators. Staff use radio collar data and observations to determine closure areas. These sites also implement wildlife flight guidelines to reduce disturbance to caribou.

Respecting these rules means you are helping caribou survive.

Protecting and mapping habitat

Caribou avoid disturbed habitats in order to dodge predators. Their movements are therefore good indicators of ecosystem health. Caribou are also an umbrella species. This means that protecting their habitat also helps the other plants and animals they live alongside.

.jpg)

Ivvavik and Vuntut National Parks in the Yukon were created, in part, to protect important parts of the Porcupine Caribou herd’s breeding and migration grounds in Canada.

To restore the habitat of the endangered Peary Caribou, Qausuittuq National Park in Nunavut is tidying the tundra from industrial waste. Watch the video below to learn more about protecting the Peary Caribou in Qausuittuq National Park.

Text transcript

0:01 The Peary caribou need help.

0:07 The herd, once 50, 000 strong, has declined by 74 percent since the 1960s.

0:13 They cover vast territories across Canada's High Artic

0:19 They have sustained Inuit for millennia.

0:24 Inuit made caribou conservation a priority within Qausuittuq National Park

0:30 The park covers 11, 000 km2 of prime caribou habitat on Bathurst Island, Nunavut

0:40 But it needs some cleaning up

0:45 Empty fuel barrels left by exploration companies litter the ground

0:49 Preventing caribou from feeding in these areas and impeding their movement.

0:57 Parks Canada and local Inuit made removing these barrels a priority.

1:02 So far, 194 empty fuel barrels have been removed from the park.

1:08 These barrels were transported by helicopter to the nearest landing strip.

1:15 From there, they were flown by aircraft to Resolute Bay for cleaning and crushing.

1:20 The community celebrated the removal of this waste material.

1:27 This important clean-up work continues.

1:33 Parks Canada is helping local youth connect to the park through engaging activities.

1:40 Inuit have lived here for millennia and will continue to do so

1:44 just like the Peary caribou.

1:51 Like. Comment. Share.

1:53 pc.gc.ca/parksinsider

1:57 Special thanks to: Canadian Wildlife Service/ L. Pirie-Dominix Government of Nunavut/ M. Anderson for the Peary caribou photographs

2:00 Parks Canada

2:02 Copyright Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada represented by Parks Canada, 2019.

2:05 Canada

Tracking the movement of caribou in Newfoundland

Parks Canada and partners have collected collar data to study the movement of the Woodland Caribou in Newfoundland.

Identifying caribou habitat helped create the Main River Waterway Provincial Park—an area just outside of Gros Morne National Park.

Watch the path that a Woodland Caribou takes as it travels inside and outside of the national park boundaries to other nearby natural areas.

Transcript

[ This video contains no spoken words ]

[bird sounds chirping in the background].

Two illustrated caribou, one parent and one calf, stand in forested vegetation. An illustrated map of Canada appears in the background, with a place marker over top of Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland.

A close-up map then shows the boundaries of Gros Morne as well as the boundaries of the Main River Waterway Provincial Park, located about 20 km outside of Gros Morne.

The movement patterns of a caribou over the course of 15 days begins to appear.

First, the caribou track is shown circling the upper reaches of Gros Morne National Park, before moving eastward outside of the park, and eventually into the Main River Waterway.

The caribou then travels inside and outside of the provincially protected park before it returns westward to Gros Morne National Park on day 15.

Movement data for this animation was generously provided by Natural Resources Canada, the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Department of Fisheries, Forestry and Agriculture.

Staff at Wapusk National Park in Manitoba are mapping caribou and their habitats with the Manitoba Métis Federation and the University of Saskatchewan. Together, they have installed a network of 92 remote trail cameras to learn how many caribou there are and where they are going.

Tag along with Parks Canada ecosystem scientists! Learn what it takes to install wildlife trail cameras in Wapusk National Park:

Text transcript

[Parks Canada beaver logo]Hey there, Russell Turner, Ecosystem Scientist for Wapusk National Park.

Currently chatting with you from Nester One Research Compound

one of four compounds in the park.

Today we're on day four of servicing our caribou trail cameras.

We have a network of 92 trail cameras out on the landscape

to document how many caribou there are and where they're going.

This work is a direct result of our Beyond Borders Caribou Workshop

where we brought together Indigenous, academic and government agencies

to chat about knowledge of caribou in the park

specifically the Cape Churchill caribou herd.

So, we have batteries, new memory cards some pliers and cutters but also spare cameras.

So today we're sampling vegetation.

So, as we go out and we find a damaged camera, we can replace it

swap out the battery, swap out memory cards.

and have all the appropriate gear to collect the right data.

Here we are, part of our caribou study is on beach ridges.

Caribou and other animals use these beach ridges as natural highways.

It's a lot easier to walk along and migrate on a gravel beach ridge

than it is walking through the fen and ponds.

We have half the cameras in fen habitats and half the cameras on these beach ridges

to document the differences of occurrence on each habitat type.

And that's my ride!

An important part of our safety plan is whenever we're in the park

we have a certified bear monitor behind me here like LeeAnn.

She's just keeping an eye out for approaching polar bears and can warn the group

when the rest of us have our head down collecting data.

One of the unique things about our study is all of our cameras

have to have these metal security boxes because

we get a lot of curious bears that like to come up and actually

bite the camera or nudge the camera to see what it is.

We also collect vegetation data.

So, we have one-meter quadrats placed on the ground

ten metres in front of each camera

so we have a little bit of information on the exact vegetation at each site

and here Matthew is behind me taking photos that we can analyze later

to figure out what vegetation is around each trail cam.

Super excited to have all those cameras done.

Hope you enjoyed our adventure today

servicing all 92 trail cameras and seeing some sights of Wapusk.

We hope to continue these projects for the next three to five years

working with our partners such as USask

and the Manitoba Métis Federation

and to come out and enjoy

beautiful days in the park like we have today.

Human activity and climate change threaten caribou numbers through habitat loss, changing food availability and increasing rates of predation, parasites and diseases.

Healthy caribou populations are integral to an overall healthy ecosystem, supporting the social and economic well-being of local communities.

Parks Canada logo

Canada wordmark

Building collaborative relationships

Many Indigenous peoples in Canada deeply value caribou. Caribou help them maintain cultural and spiritual connections to the land. With a focus on Indigenous rights and values, Parks Canada collaborates with many groups to create plans to support stewardship opportunities, like at Wapusk and Jasper.

View larger image

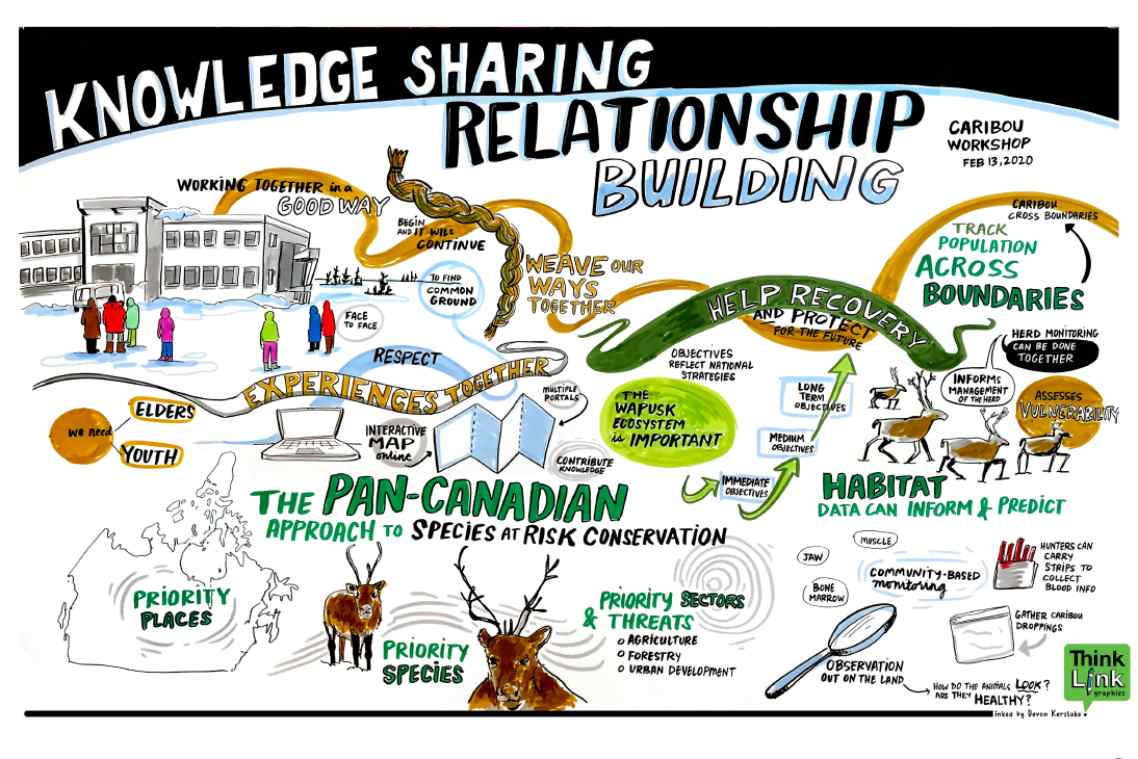

The caribou mapping project came out of the Beyond Borders Caribou Workshop hosted by Wapusk National Park. It brought together Indigenous, academic, and government agencies to share knowledge of the Cape Churchill caribou herd.

Image description

A graphic illustration titled “Knowledge sharing, relationship building” caribou workshop from Feb 13, 2020. Many smaller drawings show illustrations that represent working together in a good way, weaving our ways together, respect, experiences together, need for Elders and youth, the pan-Canadian approach to species at risk conservation, priority places, priority species, priority sectors and threats, help with recovery and protection for the future, tracking populations across boundaries, habitat data can help inform and predict, and more. Designed by ThinkLink graphics.

Remember the Torngat Mountains Caribou survey in Labrador? Parks Canada collaborated with many groups who have a hand in caribou management. This included the:

- Torngat Wildlife, Plants and Fisheries Secretariat

- Nunatsiavut Government

- Makivik Corporation

- Nunavik Parks

- Government of Quebec

- and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

Photo: Meredith Purcell

Out of sight—but never out of mind

The majority of places where Canadians live—caribou don’t. Many of us will never get the chance to see these majestic animals—but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t hold a special place in our hearts.

Caribou are resilient to Canada’s toughest climates. Yet, many caribou populations are facing steep declines—and they need our help. There are lots of ways that you can help:

- Learn about caribou in Canada and get involved in their conservation

- Share your opinions on caribou with friends, politicians, or in public consultations

- Do what you can to limit climate change

- Support initiatives that are good for mature and old-growth forests

- Practice good behaviour around wildlife so not to disturb them

- Follow rules in protected areas—slow down, stay on trails, and respect closures

- Give wildlife space. If you get the opportunity to see a caribou, do not approach them

- Report any caribou observations

- Date modified :