Microplastics: more than a drop in the ocean

Microplastics are tiny bits of plastic that come from many everyday products, from toiletries to food containers. They are getting into our oceans, lakes and rivers—which has scientists worried.

Imagine if the superhero Ant Man were to shrink himself down to the size of a rice grain and dive into a tank of seawater taken from a heavily populated coastal area.

He might find himself swimming through a surprising amount of debris.

He might bump against foam fragments as big (to him) as beach balls—the remains of coffee cups and food containers. He might get tangled in fibres from plastic clothing such as fleeces and diapers. He might have to swim around the plastic fragments from a cigarette filter.

And it wouldn’t matter if he stayed on the surface or dove underwater. The debris would be all round him, including the bottom of the tank.

Microplastics (tiny bits of plastic smaller than 5 millimetres in size) are too small to be separated out by water filtration systems. As a result, they get flushed into our lakes, rivers and oceans.

The “no-see-ums” of the plastic world

Cleaning up microplastics at Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area

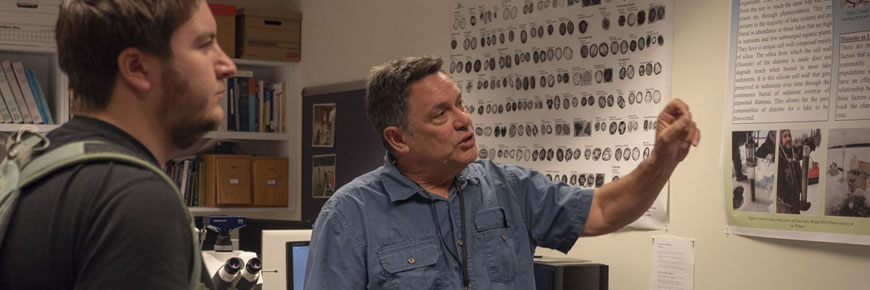

This is a concern for scientists like Dr. Marlow Pellatt, an ecological restoration specialist with Parks Canada. Dr. Pellatt studies microplastics in the coastal mud, sand and silt of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

Together with colleagues from the federal government and Simon Fraser University, Dr. Pellatt has also been looking at the concentrations of microplastics found in the sea-bottom habitat of a small West Coast fish called the Pacific sand lance in the Salish Sea.

By day, the sand lance swims eel-like through the water column, feeding on sea creatures that are as small as Ant Man (or smaller). By night, it burrows into the sea bed to sleep.

The researchers looked at concentrations of microplastics in sediments at various water depths and distances from shore. They found generally higher concentrations of microplastics in the burrowing habitats of the sand lance than in other areas.

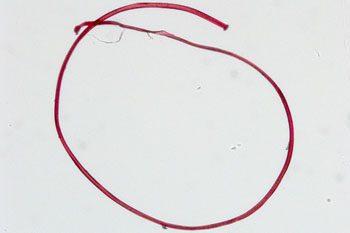

- Microfibres: tiny fibres from plastic clothing such as fleeces and diapers

- Fragments: bits of larger plastic trash that has broken down

- Nurdles: plastic pellets used to manufacture larger pieces of plastic

- Foam: bits of coffee cups and food containers

- Microbeads: tiny plastic particles found in toiletries and health products

Microplastics can be the remains of larger plastic waste that has broken down, or the tiny components of everyday products such as clothing and toiletries.

Microplastics are not limited to the waters around populated areas. Recent studies suggest that polar sea ice could be a sink for microplastics. As the planet warms and the sea ice melts, these microplastics could be released into the environment.

But there is some good news on the microplastics front.

Microbeads—tiny plastic particles found in toiletries—have been banned by the Canadian government as of July 2018. They are no longer allowed to be manufactured, imported or sold in Canada. (Microbeads in natural health products and non-prescription drugs will be banned on July 1, 2019.)

It is a first step in the fight to move Canada towards zero plastic waste.

What you can do: five easy ways to kick your plastic habits

1. If you can’t re-use it, refuse it. When you order a drink, ask for no straw.

2. Become a plastic free shopper. Bring re-usable bags when you shop.

3. Keep re-usable plastic alternatives close. Swap disposable bottles and cups for re-usable water bottles or mugs.

4. Get it in the bin. Recycle and dispose of waste properly. (Worldwide, roughly 90 per cent of new plastic products are made from fossil fuels. Recycling 1 tonne of plastic prevents up to 2 tonnes of carbon pollution.)

5. Become an advocate. Tell your friends and family what you’ve learned about the threats facing oceans, lakes and rivers.

- Date modified :