History

Port-Royal National Historic Site

In the summer of 1605, French explorers built a settlement on a beautiful river basin near the present town of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. There the soil was fertile and the natural surroundings plentiful with fish and game. Most importantly, the Mi’kmaw people whose ancestors had lived in the region for thousands of years welcomed the men and showed them how to survive in this new climate. Christened Port-Royal, it became the first European settlement north of Florida. While only in existence a few years, the settlement, and what it accomplished, proved to be a model for future exploration of the continent.

Introduction

“…this place was the most suitable and pleasant for a settlement that we had seen.”

When Samuel de Champlain wrote those words in the early 1600s, he was describing a terrain of wooded hills, meadows and a luminous stretch of water that came to be called the Annapolis River-Basin in southwest Nova Scotia. Surrounded by natural abundance with many resources—fish, fur, timber, soil—the area held a grand vision: the creation of a better world in Acadia.

First, some background…

Our story of Port-Royal begins in France during the reign of Henri IV. In 1603, Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, a nobleman, went to the king and proposed a settlement in an area called Acadia. The origins of the name reach back to the early 1500s when the Italian explorer Verrazano named a part of today’s North Carolina coast Arcadie. Subsequent maps pushed the name northeast until it came to designate what is now known as northern Maine, southern New Brunswick and mainland Nova Scotia. At the same time, it is likely that Arcadie became Acadie, or Acadia, under the influence of a local Mi’kmaw name for place.

Earlier trials by the French during the 1500s to colonize in North America had not been successful. An astute businessman, Sieur de Mons was more than determined to establish a French presence. De Mons’ plan called for private investors to finance the colony. In return, they received the monopoly for the fur trade in a vastly larger area between the 40th and 46th parallels. After much bargaining, the king granted the monopoly to Sieur de Mons, under the conditions that he establish a colony in Acadia and convert the native people to Christianity.

After raising the financing for the journey and acquiring the ships and supplies, Sieur de Mons set off to the northeastern part of North America along with a crew of workman, soldiers, artisans and explorers. Both Protestants and Catholics joined the expedition. Sieur de Mons, for example, was a Huguenot while others like Champlain, were Catholic. Although this period of religious tolerance lasted only a short while, France, under Henri IV, was the only country at the time that granted equal rights to the two religions.

In the summer of 1604, the expedition settled in Saint Croix, a small island on the Saint Croix River between Maine (USA) and New Brunswick (Canada). After a bitter cold winter, isolated on the island with no reliable source of water or fuel, nearly half of the 79 colonists died of scurvy. In the spring of 1605, accompanied by cartographer Samuel de Champlain, de Mons undertook a voyage south to find a more suitable location.

After exploring to the south and encountering hostilities from Indigenous peoples in areas of present-day Cape Cod and Maine , the explorers returned back north, where the Mi’kmaq, whose ancestors had lived in the region—known as Mi’kma’ki—for thousands of years, welcomed the new arrivals. In turn, the French reciprocated, setting in motion an enduring friendship and alliance. Given the favourable conditions, the expedition settled in a beautiful, sheltered harbour across the Bay of Fundy that they had visited briefly in 1604. Resting at the confluence of the present-day Annapolis River and Basin, this wide and sheltered swath of land possessed rich soil and abundant food sources. A long chain of high hills behind buffered the dreaded northwest wind.

The colonists named their new settlement Port-Royal. In keeping with the system of land management in New France, de Mons granted Jean de Biencourt, generally known as the Sieur de Poutrincourt, seigneury of Port-Royal.

Once Sieur de Mons settled his expedition, his small band of men (no women were on the expedition) immediately went to work reassembling buildings they had transported from Saint Croix. Needing to work with his investors and seeing the settlement rapidly taking shape, Sieur de Mons returned to France, leaving Captain François Pont-Gravé, in charge.

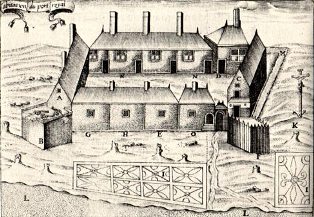

The reconstructed Habitation is based in part on Champlain's sketch.

Sketches of the Port-Royal Habitation by Champlain show a rectangular shape 18 metres (60 feet) long and 15 metres (48 feet) wide, resembling a fortified farm hamlet as seen in France during the early 1600s. At the southwest corner of the rectangle, the men built a bastion with four guns. The structure held lodgings for the settlers according to rank. Standing alone at the northern corner of the Habitation was a small house with a high-hipped roof where Pont-Gravé and Champlain lived in 1605-06. Next to their house spanned a row of smaller dwellings for gentlemen. A Catholic priest and Protestant pastor lived there, along with the surgeon Deschamps and a skilled shipwright named Champdoré. On the southwest was a dormitory for skilled workmen.

Champlain and Pont-Gravé planted gardens on the south side of the settlement. About his labours Champlain tells us, he “sowed there some seeds which throve well.” He surrounded his garden with “channels full of water, wherein I placed some very fine trout.” His servants constructed a small reservoir to hold salt-water fish. In spite of milder temperatures than what the expedition had experienced in Saint Croix, around twelve men out of 45 died that first winter in Port-Royal. Buried in the cemetery to the east of the Habitation, the deceased included a miner, the Catholic priest and the Protestant pastor.

Sieur de Mons remained in France to rally support at court and maintain ties with investors who supported the North American project. He assigned Pont-Gravé to a post on the Atlantic coast and sent over Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt, as lieutenant governor of Port-Royal. In going to Port-Royal, Poutrincourt would be visiting the land de Mons had granted him, the equivalent to having his own overseas estate. In the summer of 1606, Poutrincourt brought 50 men ashore at Port-Royal. This new contingent included his 14-year-old son, Charles de Biencourt, the lawyer and writer Marc Lescarbot, and the pharmacist Louis Hébert.

A replica of Poutrincourt’s gristmill lies near the original site on the Lequille River.

A person with broad interests, Poutrincourt came with a vision of creating a self-sustaining agricultural colony and began to work toward that end. Under his supervision, his workmen cleared large areas of land for grain and other crops upriver near present Fort Anne National Historic Site. On a small river nearby (present-day Allains River), Poutrincourt built a water-powered mill to grind the grain.

As the colony evolved, music, performance and celebration became a central part of life. In November of 1606, for example, Poutrincourt and Champlain limped back to Port-Royal after an expedition down the coast, where they had faced a hostile encounter with the Monomoyick peoples of Cape Cod. As their battered barque sailed to shore, the exuberant Lescarbot welcomed the explorers back. A family friend of Poutrincourt, Lescarbot had written a theatrical production especially for the occasion. Le Théâtre de Neptune, or The Neptune Theatre, called for a cast of eleven actors including the sea god Neptune, Tritons and Frenchmen dressed as native people. Into this lively script, Lescarbot wove classical verse, humour and poems of praise for Sieur de Poutrincourt.

A gifted musician and composer, Poutrincourt also contributed to the settlement’s artistic spirits. He wrote both religious and secular music and encouraged singing for various celebrations. Champlain too, added to the merriment by creating a dining society called the Order of Good Cheer or, L’Ordre de Bon Temps.

The Order of Good Cheer - A Taste of History

Interpreter as Champlain at the table

Proposed in the winter of 1606-07, the Order of Good Cheer provided good food and good times for the men to improve their health and morale during the long winter. Although it lasted only one winter, the society was a great success. As Lecarbot reports, every few days, supper became a feast where, on a rotating basis, everyone at the table was designated “Chief Steward.”

“This person had the duty of taking care that all around the table were well and honourably provided for. This was so well carried out, though the epicures of Paris often tell us that we had no Rue aux Ours [this street, still in existence in Paris, was the street of the rotisseurs, or sellers of cooked meat]. Over there, as a rule we made as good cheer as we could have in this same Rue aux Ours and at less cost. For there was no one who, two days before his turn came, failed to go hunting or fishing, and to bring back some delicacy in addition to our ordinary fare. So well was this carried out that never at breakfast did we lack some savoury meat of flesh or fish, and still less at our midday or evening meals; for that was our chief banquet, at which the ruler of the feast or chief butler, whom the [native people] called Atoctegic, having had everything prepared by the cook, marched in, napkin on shoulder, badge of office in hand, and around his neck the collar of the Order, ... after him all the members of the Order, carrying each a dish. The same was repeated at dessert, though not always with so much pomp. And at night, before giving thanks to God, he handed over to his successor in the charge the collar of the Order, with a cup of wine, and they drank to each other.”

The members of the Order of Good Cheer were likely prominent men in the colony. Membertou and Messamouet, Mi’kmaw chiefs in the area, were frequent guests. Earlier, Messamouet had sailed as a guide to Champlain in search of copper mines in the Bay of Fundy. As a young man, the chief told Champlain, he had journeyed across the Atlantic in a Basque fishing vessel and visited France where stayed at the home of the governor of Bayonne. Of other Indigenous guests, Lescarbot writes, “We always had twenty or thirty [native] men, women, girls, and children, who looked on at our manner of service. Bread was given them gratis [free].”

Fare for the table

The gentlemen were able to procure a wide variety of meats including: fowl (mallards, geese, partridges and other birds), moose, caribou, beaver, otter, bear, rabbit, wildcat, and raccoon. In North America at the time, beaver was a delicate meat like that of mutton. Some of the more commonly used spices then were pepper, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg. Herbs such as thyme, chervil, bay leaves and marjoram were familiar flavourings. A dish that the Habitation settlers might consider bland could well be strong or wild to our modern tastes.

Some good examples of modern dishes that might provide the flavour of a Good Cheer dinner: potage à la citrouille (pumpkin soup), anguille à létuvée (steamed eel), esturgeon

à la Sainte-Menehould (sturgeon), fricassée d’épinard (fricassee of spinach), topinambours en beignets (Jerusalem artichoke fritters), tarte à la chaire de pommes et de poires (apples and pear pie), and tarte de massepain (marzipan tarts).

Hard Times for the Colonists

Jesuit missionaries became financial partners with Poutrincourt upon his return to Port-Royal in 1610.

Just as the colony seemed capable of sustaining itself, word arrived that the King’s council had revoked Sieur de Mons’ monopoly. The news came as a devastating and bitter blow to some of the colonizers. They had built a Habitation, where the soil was good and crops flourished. For Champlain especially, it was a major setback. By the fall of 1607, the colonists were en route to France leaving the Habitation under the care of Membertou, the Kji-Saqmaw, or grand chief, of the Mi’kmaq in the Port-Royal area. Although the king reinstated Sieur de Mons’ monopoly and a member of the earlier expeditions, Champdoré, came to trade with the Mi’kmaq in 1608, the French settlement was temporarily on hold. That same year, Champlain led a group of French settlers up the St. Lawrence River, where they established the Habitation of Quebec.

Poutrincourt returned to Port-Royal in 1610 with a small expedition that included his son Charles de Biencourt, who was then about 18 or 19, and their relatives through marriage, Claude de Saint-Étienne de La Tour and his young son Charles, who would become a prominent figure in the years to come. They received a warm welcome from Membertou. Hoping to regain royal favour and financial backing, Poutrincourt persuaded Membertou, his family and several of his people to convert to Catholicism. Despite these efforts, the colony’s viability remained on shaky grounds. Jesuit interest in establishing missions in Acadia and their influence at Court ensured their participation. Through their royal connections, they became financial partners of a wary and reluctant Poutrincourt. The arrival and subsequent involvement of Fathers Massé and Biard in local affairs at Port-Royal made existing internal conflicts worse. Ultimately, the colony lost its financial support due to conflicts between the Biencourts (Poutrincourt and his son Charles) and the Jesuits. In May 1613, a relief ship removed the Jesuits to Penobscot (Maine) where they founded another settlement named Saint-Sauveur. In July, Samuel Argall of Virginia, commissioned to expel all Frenchmen from territory claimed by England, attacked and destroyed the colony.

Coats of arms at the Habitation

That fall, while the inhabitants of the Port-Royal settlement were away up river, Argall’s expedition sailed into Port-Royal and looted and burned the Habitation. Poutrincourt, who was in France, returned in the spring of 1614 to find his Habitation in ruins, and his son and companions living with the Mi’kmaq. Discouraged, he returned to France. Poutrincourt transferred his land holdings and leadership role in Acadia to his son, Charles de Biencourt. At that time, the area encompassed principally mainland Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and coastal parts of Maine. Charles de Biencourt remained in the region with his cousin and second in command, Charles de Saint-Etienne de La Tour and a handful of men. When Biencourt died in 1623, La Tour became leader of the colony and continued the fur trade in the region. He founded a trading base at Cape Sable and later, one on the Saint John River.

The settlements at Saint Croix, Port-Royal and Quebec marked the beginnings of French settlement on the continent. The generations that followed would firmly ensure the integration of French culture in North America.

Related links

- Date modified :