People of significance

Port-Royal National Historic Site

Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons

Samuel de Champlain

Membertou

Marc Lescarbot

Jean de Poutrincourt

Louis Hébert

François Gravé, Sieur du Pont

Père Pierre Biard

Costumed interpreters at Port-Royal

The creation of the first permanent French settlement in North America was made possible by the extraordinary efforts of a brave band of explorers. Highly energetic and enterprising, these individuals were integral in carving out the foundation of future European expansion into Canada; one that integrated a philosophy of tolerance and cooperation toward native people. While the contributions made by each of the individuals in this section vary, they would not have been possible without the collective vision of men like Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons and Samuel de Champlain, who were determined to create a more enlightened world than the one they left behind.

Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons

Bust of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons

Bust of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons © Parks Canada/T. Bunbury

A bronze bust of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons rests on a grassy knoll overlooking the Annapolis River at Fort Anne National Historic Site. The memorial’s prominence is symbolic of the bold accomplishments made by this French explorer, merchant and visionary. His expedition here in 1604, which included navigator and cartographer Samuel de Champlain, played a major role in motivating France’s interest in exploring North America, and in providing a base of knowledge that would greatly influence the development of Canada. Predating the founding of both Quebec and the English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, the region—under de Mons’ energetic guidance— became home to one of the first permanent European settlements north of Florida and a critical portal to European exploration and settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Born into the French aristocracy, de Mons had fought for Henry IV, had served as an administrator and knew how to work with investors. These factors became the pivotal mix when he and Champlain approached the king in 1603 to promote a plan to explore North America. Able to convince private investors to finance the colonization in return for a monopoly over the fur trade, de Mons focused on Acadia. The region rested along the same latitude as his home province of Saintonge, a place with mild winters and fertile soil.

While the choice to settle on Saint Croix Island resulted in tragedy, it was no doubt instructive in understanding the region’s natural variations. Prior to Saint Croix, de Mons had explored the sheltered harbour Marc Lescarbot credits him with naming Port-Royal and it became his next choice. Once ashore, the settlers wasted no time in building a settlement there and a base for further discovery. Between 1605 and 1607, the French in Port-Royal set about expanding the fur trade, exploring and mapping the Atlantic coastline, searching for valuable minerals, and developing an agricultural colony. Most importantly, they learned to live peacefully with the Mi’kmaq, who repeatedly demonstrated their friendship.

Referring to the task undertaken by de Mons to promote a French settlement, explore the land and expand commerce, Marc Lescarbot writes in the dedication of his poem Adieu à la France (1606):

“… it is you whose high courage has traced the way for such a great undertaking, and for this reason, in spite of the attack of time, the leaf of your fame will grow green in an eternal spring.”

In 1607, Henri IV, in response to the protests of rival French merchants, revoked de Mons’ fur trade monopoly forcing him to order his Port-Royal settlers back to France. In the ensuing years, Sieur de Mons continued to aid and support Champlain in developing New France. Forward thinking and open-minded, he made a substantial contribution to the development of Canada by proving that Europeans could live here and sustain themselves successfully.

For more information on Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Samuel de Champlain

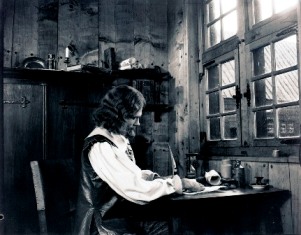

Site interpreter re-enacting Champlain’s recollections of Port-Royal

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

Samuel de Champlain made the first of an estimated 29 crossings of the Atlantic Ocean in 1598 on a voyage to the West Indies. In 1603 he traveled much farther north as a royal geographer on a fur trading expedition to the St. Lawrence River. The expedition sailed to Tadoussac, at the mouth of the Saguenay River, which had long been a trading center for the indigenous peoples living along the St. Lawrence. His next voyage would take him to Acadia.

By the time Champlain settled in Port-Royal in 1605, he had already mapped a large portion of the northeastern coast of North America. Consumed with curiosity and an irrepressible spirit of adventure, he continued to sail and chart the coasts, using Port-Royal as a base. He spent three years at Port-Royal where he lived in comfort. Champlain created for himself a work-room among the trees, and built a sluice to stock his own trout. He took “a particular pleasure” in gardening. At the same time, he developed amiable relations with the local indigenous people and they, in turn, taught him much about living and surviving in this new environment.

During the summer of 1606, Jean Biencourt de Poutrincourt arrived as lieutenant governor. In September 1606, Poutrincourt and Champlain searched southward for a new settlement sailing along the present-day New England coast and rounding Cape Cod. The expedition headed back north after a bloody scrimmage with the Monomoyick peoples in Port-Fortuné (present day Chatham, MA) in which several crew members died.

Bust of Champlain at Port-Royal

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

The winter of 1606-07 was a joyful one highlighted by moderate temperatures and food and wine in abundance. Champlain added to the high spirits by founding the Order of Good Cheer, or L’Ordre de Bon Temps, a dining society whose members took turns providing game for the table and maintaining an atmosphere of merriment. In the spring of 1607, de Mons’ trading privilege was revoked, forcing him to order his settlers back to France. Before leaving, however, Champlain went back to the Baie Françoise (Bay of Fundy) to look for a copper mine, but found only nuggets. Champlain’s partnership with Sieur de Mons would continue on an auspicious path. The next year, with financial backing obtained by de Mons, Champlain returned to the St. Lawrence and began to build a settlement that would mark the founding of Quebec.

Unlike his English and Spanish contemporaries, Champlain was more interested in learning from and cooperating with native people than in exploiting them. He envisioned a world where people of different faiths and races could live and mix together. Today Champlain is remembered as the father of New France.

For more information on Samuel de Champlain please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Membertou

What we know today about the grand chief or kjisaqmaw, Membertou, is based primarily on the writings of Marc Lescarbot and other explorers. Nearly all of them described him as a person of great influence, who led a small following of Mi’kmaq in the region that came to be known by the French as Port-Royal. According to reports, Membertou was very old, though vigorous, when Sieur de Mons moved his expedition across the bay to establish the Habitation at Port-Royal. Champlain wrote that in war Membertou “had a reputation of being the most evil and treacherous among all those of his nation.” His trustworthiness in dealings with friends, neighbours and guests earned him the esteem of the French. Father Biard, one of the Jesuits who came to Port-Royal in 1611 wrote: “This was the greatest, most renowned and most formidable [native person] within the memory of man; of splendid physique, taller and larger-limbed than is usual among them; bearded like a Frenchman, although scarcely any of the others have hair upon the chin; grave and reserved; feeling a proper sense of dignity for his position as commander.”

Images from the book, "The Micmac And How Their Ancestors Lived Five Hundred Years Ago"

© Parks Canada/K. Kaulbach

After the settlers received orders to return to France in 1607, the Port-Royal Habitation was left for three years in Membertou’s hands. He greeted the French on their return to Port-Royal in June of 1610. On June 24th, 1610 (Saint John the Baptist Day), Membertou became the first Aboriginal person to be baptized in New France. The ceremony was carried out by Father Jessé Fléché, who had just arrived on Poutrincourt’s expedition. Fléché went on to baptize all of Membertou’s immediate family. Membertou was given the baptized name of the late king of France, Henri, as a sign of alliance and good faith. A year later, Membertou became gravely ill. While he originally insisted on being buried with his ancestors, Jesuit missionaries persuaded him otherwise. Close to his death, Membertou requested to be buried among the French. In his final words he charged his children to remain devout Christians. The grand chief’s conversion to Christianty has had a lasting impact on the Mi’kmaq culture. Today many Mi’kmaw people continue to practice Roman Catholicism.

Resources:

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

Mi’kmaq Resource Centre

Marc Lescarbot

A Parisian lawyer and writer, Marc Lescarbot cultivated a wide circle of friends that included writers and nobility. When one of his clients, Jean de Poutrincourt, who was associated with the enterprises of the Sieur de Mons, proposed that he accompany them on a voyage to Acadia, Lescarbot quickly accepted. He composed a poem, Adieu à la France, and embarked at La Rochelle in May of 1606. He reached Port-Royal two months later and stayed there until 1607, when the revocation of Sieur de Mons’ monopoly obliged the colony to go back to France.

Costumed interpreter portraying Marc Lescarbot

© Parks Canada

Lecarbot wrote the Théâtre de Neptune (Neptune Theatre) to celebrate Poutrincourt’s return to Port-Royal after a traumatic expedition to the south. The story revolves around the god Neptune who comes in a small boat to welcome the travellers home. He is surrounded by a court of Tritons and Indians, who praise the leaders of the colony, and then sing in chorus while trumpets sound and cannons are fired. Performed in the impressive setting of the Port-Royal basin, it became the first European theatrical presentation in North America.

On his return to France he began writing Histoire de la Nouvelle-France (History of New France). In the second edition of the book, he undertook to recount de Mons’ ventures in Acadia, based on the year he spent in Port-Royal and interviews with the promoters and members of the earlier voyages, François Pont-Gravé, de Mons, and Champlain. Lescarbot devoted the whole of the last part of his History to a description of the native people. He was keenly interested in their customs, phrases, chants, and foremost, their humanity.

Here he writes:

“These people…are men like ourselves…They have courage, fidelity, generosity, humanity and their hospitality is so innate and praiseworthy that they receive among them every man who is not an enemy. They are not simpletons like many people over here; they speak with much judgment and good sense.”

Years after he returned to his home in France, Lescarbot seemed to hope that he had started something that day in 1606 with his Neptune Theatre. He wrote “Yet if it come to pass that there should come a day among the mountains and brooks of Port Royale, that the Muses ... grow more gentle ... then in their songs, let them remember me.”

All told, Lescarbot is most remembered for writing and producing one of the earliest European plays in North America and for writing one of the first great books on the history of Canada.

For more information on Marc Lescarbot please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Jean de Poutrincourt

In 1603, Jean de Poutrincourt, a baron and soldier, learned that his friend Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons had received a grant to explore Acadia and was planning an expedition to the region. With great aspirations to found an agricultural colony in North America, he appealed to Henri IV and received permission to accompany de Mons. Energetic and industrious, Poutrincourt obtained the necessary arms and soldiers for the defence of the settlement de Mons planned to establish.

A monument dedicated to Poutrincourt located near the site of his grist mill on the Lequille River

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

The expedition set sail in early March, 1604. After four long months, it reached the north Atlantic coast of North America around the 45th parallel. As the expedition searched for an area to settle in for the winter, it sailed into a narrow passage between two high cliffs. Here they entered into what Champlain described as, “…one of the finest harbours I had seen on all these coasts.” Because of its regal dimensions, Champlain named it Port-Royal.

Poutrincourt was so impressed with the beauty of the country, he asked for and was given a grant to the territory by the Sieur de Mons on his promise to colonize Port-Royal. The king confirmed this grant, in 1606, which included fur-trading privileges and fishing rights. While de Mons and most members of the expedition decided to spend the winter on an island they named Saint Croix, Poutrincourt returned to France that autumn with a cargo of furs.

In the spring of 1606, Poutrincourt returned to Port-Royal as lieutenant governor of Acadia to take command of the new settlement at Port-Royal. He brought with him some 50 men including Louis Hébert, Marc Lescarbot, and his own son Charles de Biencourt, and set out to strengthen the settlement. He erected a number of buildings; among them was a water-driven grist-mill, possibly the first in northern North America. Under his supervision, the settlers prepared fields and planted crops. He made friends with the native people and garnered their trust. The French under Poutrincourt set a pattern of good will.

In the autumn of 1607, the ship Jonas arrived in Acadia, with the news that the King’s council had revoked Sieur de Mons’ trading monopoly. The inhabitants of Port-Royal were forced to return to France. Despite the setback, Poutrincourt held fast to his dream of settling Acadia. Poutrincourt did not return to Acadia until 1610. The delay was due in part to trouble with financial backers and his disinclination to take the Jesuits with him. Though they had great influence with the king, who insisted they go to Port-Royal, the Jesuits were rumoured to be too interested in commercial profit. Nevertheless, once he arrived back in Port-Royal, Poutrincourt worked hard to build his agricultural colony and set about converting the native people with a new zeal. The old chief Membertou was baptized along with twenty members of his family.

The struggle between Poutrincourt and the Jesuits and their allies however, would overpower the settler’s mission, forcing him to return to France discredited. Undaunted, Poutrincourt formed a partnership with ship outfitters in France by promising them a share of the fur trade in the Port-Royal region, which he still controlled. In December, 1613, he again set sail for Port-Royal. He arrived that March to find the Port-Royal Habitation in ruins and the inhabitants starving after Samuel Argall’s raid the previous November. Poutrincourt had no choice but to return to France with most of the colonists. He deeded to his son the title of all his lands in North America.

Poutrincourt died in 1615. His son, Charles de Biencourt, remained in Acadia and continued on with the fur trade until his death in 1623, at around the age of 31.

For more information on Jean de Poutrincourt please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Louis Hébert

Hébert’s apothecary at Port-Royal

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

In 1606, Louis Hebért, a second-generation French apothecary, may have been the first European with such skills in North America. His father, Nicolas Hébert, served as the royal apothecary to the court of Catherine de Medicis. Louis Hébert, in turn, trained in medical arts and science, becoming a specialist in pharmacology. His profession instilled a life long love of plants and gardening. Connected by marriage to Jean de Poutrincourt and by friendship to the Sieur de Mons and Champlain, Louis Hébert was a true believer in the idea of New France.

He was part of Poutrincourt’s expedition to Port-Royal that also included Marc Lescarbot. On a map of the region, Lescarbot indicates a river and an island named for Hébert running across the Dauphin River (Annapolis River) from Port-Royal. Today we know them as Bear River and Bear Island.

Site interpreter inside Hébert’s apothecary

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

At Port-Royal, Hébert looked after the health of the pioneers and native people, treating both equally. He cultivated native drug plants, and supervised the gardens. He examined specimens of drug plants offered by the Mi'kmaq. Lescarbot writes with awe of Hébert’s pleasure in cultivating the soil and his adept healing skills. Hébert cared for chief Membertou during his last illness.

In 1613, when Samuel Argall raided and destroyed the settlement, Hébert and most of the colonists were forced to return to France. The lure of Canada was strong, however, and in 1617, he and the family returned with Champlain to Quebec, where Hébert gained lasting recognition as one of the first successful European farmers in Canada.

For more information on Louis Hébert please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

François Gravé, Sieur du Pont

Pont-Gravé encouraged inhabitants to plant gardens for their own gain

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

A courageous seaman with long experience in the North Atlantic and a major figure in the colonization of New France, François Pont-Gravé served as commander of Port-Royal from 1605 to 1606. The young Samuel de Champlain after sailing with Pont-Gravé on an earlier expedition to the St. Lawrence, referred to the more seasoned mariner as his mentor. “As for the Sieur du Pont,” Champlain would write, “I was his friend and his age led me to respect him as I would my father.”

After entrusting Pont-Gravé with the command of Port-Royal, de Mons returned to France to build support and financing for the expedition. Pont-Gravé kept the workmen busy on the settlement, urging them to weather proof the Habitation before winter. He also created gardens outside the fort and encouraged the colonists to till individual plots for their own gain.

Large spirited with a gift for storytelling, Pont-Gravé was popular with the men even though he had a temper. “M. du Pont was not a man to sit still, nor allow his people to remain idle,” Marc Lecarbot wrote.

The period that Pont-Gravé headed Port-Royal proved difficult. After many months of waiting for supply ships from France, Pont-Gravé feared the settlement would run out of provisions. The commander and all but two of the colonists boarded small boats, called barques, and set sail for Canso where they hoped to find anglers who could help them. En route, they ran into a sharp squall, and the high seas damaged one of their iron rudders. They sailed on, very near starvation. Finally, a French ship appeared reporting that a supply ship was en route with abundant provisions.

Still their leader, Sieur de Mons decided to stay in France to work with his investors. In 1606, he ordered Pont-Gravé to run commercial operations on the fishing coast. Two years later, Pont-Gravé commanded one of the ships; and Champlain commanded the other, on an expedition that led to the founding of Quebec.

For more information on François Gravé, Sieur du Pont please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Père Pierre Biard

Confessional, altar, tabernacle and crucifix inside the Habitation’s chapel

© Parks Canada/A. Rierden

In 1608, Henri IV’s confessor summoned Pierre Biard, a Jesuit priest and scholar in theology and Hebrew, to take charge of the Jesuit mission in Acadia. The Jesuits had a powerful ally at court, Antoinette de Pons, Marquise de Guercheville, the wife of the governor of Paris, and the first lady-in-waiting to the queen. Deeply religious, she supported the Order’s desire to found missions in North America and raised money at court so that Biard and Father Énemond Massé could become partners with Poutrincourt in the New France expedition after other backers had withdrawn. Eventually, through Madame de Gurercheville’s patronage, the Jesuits obtained passage by becoming part owners of the ship and cargo. They arrived in Port-Royal in May of 1611. Father Biard would become the first in a long line of distinguished Jesuits to write accounts of North America and the first to describe native people.

The priests’ tenure at Port-Royal, however, would not be easy. Conflicts with Charles de Poutrincourt over the standards used to convert the native people (in Poutrincourt’s eyes, the higher the numbers the better the chances of obtaining court financing) and the overall mood of suspicion and prejudice between the colonists and the priests, resulted in the Jesuit mission meeting with little success. Madame de Guercheville, who had succeeded Sieur de Mons as proprietor of New France, eventually sent over another vessel in 1613 under Réne Le Coq , Sieur de La Saussaie, and ordered him to stop at Port-Royal to take the two Jesuits elsewhere to found a new colony. La Saussaie sailed over to what is now Bar Harbor, Maine. Their colony, Saint-Sauveur, had barely set down roots when Samuel Argall from Virginia plundered the establishment in a quest to destroy all French settlements in the region. Argall sent half the settlers with Father Massé adrift in a small boat that eventually made it to France. He took the other half with Father Biard as prisoners to Jamestown, Virginia. Another Argall expedition with Biard on board, set out soon after to complete the destruction of Saint Croix and Port-Royal.

After Argall destroyed Port-Royal, he sent Biard back to Jamestown, where he may have faced execution. However, stormy seas and high winds carried the vessel on which he was held as prisoner across the ocean to the Azores. Eventually the captain released Biard.

Back in France, he met with scorn for purportedly helping in the demise of Port-Royal. Champlain, however, vindicated him. Biard resumed his work as a professor of theology, and afterwards became a prominent missionary in the south of France. Toward the end of his life, he was made military chaplain in the armies of the king.

For more information on Père Pierre Biard, please go to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

Related links

- Date modified :