Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Management Plan, 2023

Quttinirpaaq National Park

On this page

- Foreword

- Recommendations

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Significance of Quttinirpaaq National Park

- Planning context

- Development of the management plan

- Vision

- Key strategies

- Zoning

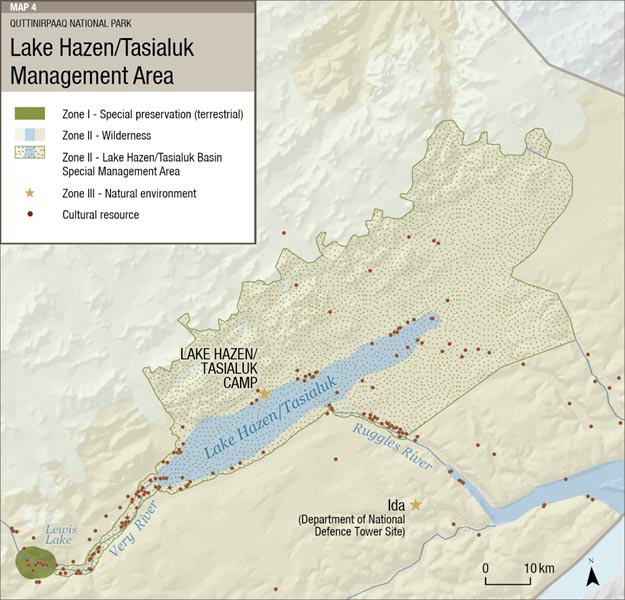

- Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Management Area

- Summary of strategic environmental assessment

Note to readers

The health and safety of visitors, employees and all Canadians are of the utmost importance. Parks Canada is following the advice and guidance of public health experts to limit the spread of COVID-19 while allowing Canadians to experience Canada’s natural and cultural heritage. Parks Canada acknowledges that the COVID-19 pandemic may have unforeseeable impacts on Quttinirpaaq Historic Site of Canada Management Plan. Parks Canada will inform Indigenous peoples, partners, stakeholders and the public of any such impacts through its annual implementation update on the implementation of this plan.

This document refers to articles of the 1993 Agreement Between the Inuit of the Nunavut Settlement Area and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Nunavut Agreement) and the 2001 Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks (Baffin IIBA). These documents provide a frame of reference and outline obligations for cooperative management of national parks in Nunavut. It is recommended that readers familiarize themselves with these documents to fully understand the context for managing Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada.

Foreword

From coast to coast to coast, national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas are a source of shared pride for Canadians. They reflect Canada’s natural and cultural heritage and tell stories of who we are, including the historic and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples.

These cherished places are a priority for the Government of Canada. We are committed to protecting natural and cultural heritage, expanding the system of protected places, and contributing to the recovery of species at risk.

At the same time, we continue to offer new and innovative visitor and outreach programs and activities to ensure that more Canadians can experience these iconic destinations and learn about history, culture and the environment.

In collaboration with Indigenous communities and key partners, Parks Canada conserves and protects national historic sites and national parks; enables people to discover and connect with history and nature; and helps sustain the economic value of these places for local and regional communities.

This new management plan for Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada supports this vision.

Management plans are developed by a dedicated team at Parks Canada through extensive consultation and input from Indigenous partners, other partners and stakeholders, local communities, as well as visitors past and present. I would like to thank everyone who contributed to this plan for their commitment and spirit of cooperation.

As the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, I applaud this collaborative effort and I am pleased to approve the Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Recommendations

Joint Park Management Committee

In accordance with the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks (Baffin IIBA), the Joint Park Management Committee is pleased to approve the Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Signed on behalf of the Committee by:

Tabitha Mullin

Chair

Quttinirpaaq Joint Park Management Committee

Parks Canada

Recommended by:

Ron Hallman

President & Chief Executive Officer

Parks Canada

Andrew Campbell

Senior Vice-President, Operations Directorate

Parks Canada

Jenna Boon

Superintendent, Nunavut Field Unit

Parks Canada

Nunavut Wildlife Management Board

June 15, 2023

The Honourable Steven Guilbeault

Minister of Environment and Climate Change

Canada Government of Canada

RE: NWMB Decision on the Proposed Management Plan for the Quttinirpaaq National ParkDear Steven Guilbeault:

NWMB Decision

At the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board’s (NWMB or Board) Regular Meeting (RM 002-2023) on June 7, 2023, Parks Canada requested that the NWMB approve the final draft of the Quttinirpaaq National Park Management Plan (Management Plan). The NWMB considered the request for approval at its In-Camera Meeting (IC 002-2023) on June 7, 2023, and made the following decision:

Resolved that, pursuant to Section 5.2.34 (c) of the Nunavut Agreement, the NWMB approve the Quttinirpaaq National Park Management Plan.

Reasons for the NWMB's decision

Based on the information presented by Parks Canada staff at the Regular Meeting, the Board understand that:

- according to the Canada National Parks Act, Parks Canada Agency Act, and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks the Management Plan must be reviewed by the Quttinirpaaq Joint Park Management Committee every 10 years

- the management plan’s purpose is to provide clear direction for protecting and managing the parks’ ecosystems

- the management plan’s key strategies are honouring shared commitments, working together, and learning from people and land

- Inuit rights to use the Quttinirpaaq National Park for traditional activities, including harvesting are not restricted

The Board also heard and appreciates the level of Inuit involvement in the planning process. The Board is aware that the Quttinirpaaq Joint Park Management Committee has already approved the draft Management Plan. The Board was also pleased to hear that one of the targets in the Management Plan is to seek opportunities to support the re-establishment of historical human ties to Greenland, as many Inuit in Grise Fiord have relatives in Greenland.

The Board has determined that the Management Plan will facilitate local involvement in the management of the Quttinirpaaq National Park and the protection of wildlife and wildlife habitats and wishes you good luck in its implementation.

Conclusion

The NWMB is forwarding its decision to you for your consideration pursuant to the terms of the Nunavut Agreement. Please contact the NWMB if you have any questions concerning the contents of this letter.

Executive summary

Located on northern Ellesmere Island, Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada is the country’s northernmost national park, representing the Eastern High Arctic Natural Region in Canada’s National Park System Plan. Initially established as a National Park Reserve in 1988, Quttinirpaaq National Park protects 37,775 square kilometres, and is the country’s second-largest national park. The park’s landscape is dominated by glaciers and mountains and includes a variety of uniquely adapted ecosystems, resulting in protection of substantial biodiversity.

Together, Parks Canada and Inuit are managing Quttinirpaaq National Park through the Joint Park Management Committee as outlined in the Nunavut Agreement and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks (Baffin IIBA). This management committee advises the Minister on any matters pertaining to park management for ministerial approval.

This management plan replaces the 2009 management plan for Quttinirpaaq National Park and reflects the priorities of Parks Canada and Inuit partners. The plan outlines the importance of Quttinirpaaq to multiple groups, including Inuit from the adjacent communities of Resolute and Grise Fiord, whose ancestors lived here. Quttinirpaaq is a place of global importance to understand the impacts of climate change.

The 10-year vision articulated in this plan underlines the importance of conservation, partnerships, and enhancement of opportunities for appreciation and understanding of the park’s natural and cultural significance. Three key strategies, a zoning plan, and an area management approach are identified to guide management activities to realize the park’s vision.

Key strategy 1

Honouring shared commitments

Core objectives of the Nunavut Agreement are to encourage self-reliance and to support the cultural and social well-being of Inuit. This strategy addresses Parks Canada’s goals to meet its Nunavut Agreement and Baffin IIBA obligations. Parks Canada works with other federal government departments to be an active member of the associated communities of Resolute and Grise Fiord.

Key strategy 2

Working together

Conservation is more successful when aligned with regional initiatives for activities inside and outside the park. Quttinirpaaq management will be guided by the Inuit Societal Value of Qanuqtuurniq (being innovative and resourceful) to proactively seek out ways to work with others to ensure continued success. Effective two-way communication and relationship building with communities are essential to realize this success.

Key strategy 3

Learning from people and land

Quttinirpaaq management will bring together science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit to foster Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq (respect and care for the environment) and increase our understanding of the natural and cultural values of the park and the greater region. This knowledge will be used to encourage global appreciation and understanding of the High Arctic, the impacts of climate change, and humanity’s ingenuity and ability to adapt to challenges and changing circumstances.

1.0 Introduction

Parks Canada administers one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic places in the world. Parks Canada’s mandate is to protect and present these places for the benefit and enjoyment of current and future generations. Future-oriented, strategic management of each national historic site, national park, national marine conservation area and heritage canal administered by Parks Canada supports its vision:

Canada’s treasured natural and historic places will be a living legacy, connecting hearts and minds to a stronger, deeper understanding of the very essence of Canada.

The Canada National Parks Act and the Parks Canada Agency Act require Parks Canada to prepare a management plan for each national park. Implementing the Nunavut Agreement requires this management plan to be developed by a Park Planning Team, consisting of an equal number of members appointed by Parks Canada and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association. The Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Management Plan has been reviewed by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, and approved by the Quttinirpaaq Joint Park Management Committee and the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board; once approved by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada and tabled in Parliament, it will ensure Parks Canada’s accountability to Canadians, outlining how park management will achieve measurable results in support of its mandate, as well as in the implementation of the Nunavut Agreement and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks (Baffin IIBA).

This national park is managed with the Quttinirpaaq Joint Park Management Committee who have been involved in the preparation of the management plan to shape the future direction of the heritage place. Partners, stakeholders, Inuit from the adjacent communities of Resolute and Grise Fiord, and the Canadian public have also been involved in the preparation of the management plan. The plan sets clear, strategic direction for the management and operation of Quttinirpaaq National Park by articulating a vision, key strategies, and objectives. Parks Canada will report annually on progress toward achieving the plan objectives and will review the plan every ten years or sooner if required.

This plan is not an end in and of itself. Parks Canada will maintain an open dialogue on the implementation of the management plan, to ensure that it remains relevant and meaningful. The plan will serve as the focus for ongoing engagement and, where appropriate, consultation, on the management of Quttinirpaaq National Park in years to come.

It’s a beautiful land if it’s a beautiful day. But if it’s a bad day, it’s still a beautiful land.

2.0 Significance of Quttinirpaaq National Park

Quttinirpaaq National Park is Canada’s northernmost and second largest national park, covering an area of 37,775 square kilometres (Map 1). Quttinirpaaq is an Inuktitut word meaning “at the top,” referring to its location at the top of the world. It was named by the people of Grise Fiord and Resolute in 2001. The park’s landscape is dominated by glaciers and mountains yet includes a remarkable diversity of unique and localized ecosystems, including a polar desert, the deepest freshwater lake north of the Arctic Circle, and distinct microbial systems. Along the northern coast, glaciers spill into deep marine fiords, and multi-year shelves support unique, ice-dependent communities. Some of the area’s lowlands and wetlands are surprisingly lush, with a remarkable variety of plants and animals for a region shrouded in snow and darkness for half the year. Muskoxen, small herds of Peary caribou, Arctic wolves, Arctic hares, and a variety of birds can be found here.

Quttinirpaaq plays a significant role in understanding human history in the Arctic, with some of the oldest and one of the densest concentrations of prehistoric Arctic archaeological sites within its boundary. Dating back over 4,000 years, these sites provide evidence of the migration of Independence I people from the sub-Arctic to Greenland along a route known as the Muskox Way. The area is important to today’s Inuit as their direct ancestors, Thule Inuit, travelled and lived here for several hundreds of years; they came to this area about 1,000 years ago and evidence of their year-round presence is found throughout the park. The Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Area (Map 4) has been an important hunting and fishing ground for Greenland Inughuit until quite recently.

This region became better known to southern Canadians in the era of the Cold War (1947–1991) due to the Canadian Defence Research Board, who established three camps in what is today Quttinirpaaq National Park. The Canadian Defence Research Board conducted integrated scientific research spanning meteorology, glaciology, oceanography, and other disciplines between the 1950s and 1970s. Their research, and subsequent studies in these northernmost ecosystems, has been informing science for well over six decades. The park is viewed as a global point of reference for the effects of climate change. As the impacts of climate change are more pronounced near the poles, observations made this far north can provide a window into changes and challenges anticipated for southern regions.

Quttinirpaaq National Park represents the Eastern High Arctic Natural Region within the Canadian National Park’s System Plan. The park’s eastern shores and ice shelves are within the Remnant Arctic Multi-Year Sea Ice and Northeast Water Polynya Ecoregion, which the International Union for Conservation of Nature proposes to have outstanding universal value. Fisheries and Oceans Canada considers this ecosystem an Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area of the Arctic Archipelago Region.

Quttinirpaaq National Park was first established as a Park Reserve in 1988. Following the signing of the Nunavut Agreement in 1993, the Baffin IIBA was negotiated with the Qikiqtani Inuit Association and signed in 1999. Quttinirpaaq was subsequently established as a national park with a cooperative management committee (the Joint Park Management Committee) when the Canada National Parks Act came into force in 2001. The park is a tangible expression of Canadian Arctic Sovereignty.

In 2004, Canada included Quttinirpaaq National Park on its tentative list for future nomination for inclusion on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) list of World Heritage Sites. Proposed under four separate criteria – successive human occupation, natural beauty and superlative natural phenomena, geological processes representing major stages of earth’s history, and the presence of a diversity of arctic species – Canada believes that the natural and cultural values of Quttinirpaaq are globally significant.

3.0 Planning context

Remote location

As one of the most remote and least visited national parks in Canada, Parks Canada faces some unique challenges with Quttinirpaaq National Park. There are no roads to get to the park, and no aircraft stationed in Grise Fiord, which is the closest community at over 600 kilometres away. The airport in Resolute, where charter flights to the park depart, is over 900 kilometres away, resulting in significant financial and environmental operating costs.

Legislative basis of the park

The Canada National Parks Act and associated regulations provide the legal framework for managing Quttinirpaaq National Park. Importantly, the Nunavut Agreement prevails where any legislative inconsistencies or conflicts arise. Specific zoning parameters are outlined in the Nunavut Agreement, stating that “each National Park in the Nunavut Settlement Area shall contain a predominant proportion of Zone I – Special Preservation and Zone II – Wilderness.”

Cooperative management

The Nunavut Agreement defines the rights of Inuit and formalizes the arrangement for potential joint Inuit/Government parks planning and management of Parks Canada places in Nunavut. The Baffin IIBA defines this management structure and establishes the requirements, composition, and responsibilities of a Joint Park Management Committee. The Joint Park Management Committee, like the Park Planning Team, consists of an equal number of members appointed by Parks Canada and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, who act impartially and in the public interest, rather than as representatives of their appointing body. The Joint Park Management Committee advises on all matters relating to park management, including the development of this plan. The Baffin IIBA further outlines the management plan development and approval process for Quttinirpaaq and request the plan be approved by the Joint Park Management Committee before public consultation and before ministerial approval.

Benefits for Inuit in Nunavut

An objective of the Baffin IIBA is to provide opportunities for Inuit in the adjacent communities to benefit from the establishment, planning, management, and operation of the park. The two adjacent communities, as defined by the Baffin IIBA, are Resolute and Grise Fiord. Both have populations under 200. As previously stated, these communities are still a substantial distance from the park, and few Inuit go to the park as they face the same access challenges as Parks Canada. Currently, the park’s operating season is limited to two months in the summer, which can still be a long time away from home for staff from a culture with strong family ties. No Quttinirpaaq-specific positions are based in either community. The above factors all contribute to the challenge of recruitment, retention, and community engagement. This management plan is a renewed commitment from Parks Canada to do better in fulfilling benefits for Inuit through the specific targets outlined herein, including implementation of a renewed Nunavut Field Unit Inuit Employment Plan (2019).

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit refers to the knowledge and understanding of all things that affect the daily lives of Inuit, and the application of that knowledge for the survival of a people and their culture. It is a knowledge that has sustained the past and that is to be used today to ensure an enduring future. Incorporating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit into the management of Quttinirpaaq National Park is a priority. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit should be an overarching planning tool that influences all other priorities. Many targets in this management plan are aimed at better incorporating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit into the management of the park.

Landscape-level conservation initiatives

Quttinirpaaq National Park is not the only site administered by Parks Canada in the High Arctic region of Nunavut: Qausuittuq National Park on Bathurst Island was established in 2015 following the ratification of a separate Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement that outlines obligations similar to the Baffin IIBA, and the Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area is associated with not only Resolute and Grise Fiord, but also Pond Inlet, Arctic Bay, and Clyde River. In addition, Tuvaijuittuq, the High Arctic Basin off the northern shores of the Arctic Archipelago, came under interim protection in 2019 as a Marine Protected Area through the authority of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. These new protected areas significantly change the conservation landscape and, alongside the already established Migratory Bird Sanctuaries and National Wildlife Areas, provide opportunities for federal departments and agencies to effectively work together with and within the same adjacent communities.

Climate change

The effects of climate change are directly impacting the environment of the park as well as its users. Staff at the main operations camp and visitor hub, Tanquary Fiord, are seeing changes to the freshwater source, which will require attention within the lifespan of this management plan. Erosion events witnessed throughout the park are thought to be increasing, a belief substantiated by Parks Canada’s work at Fort Conger and other recent studies in the Canadian Arctic. Fort Conger is both a cultural and a contaminated site on the eastern shore of the park (Map 2), where monitoring reveals an eroding coastline that is increasing the risk of contaminants being deposited into the Arctic Ocean. Parks Canada staff anticipate future changes but cannot predict the level of change. Increased attention to asset management and safety is therefore warranted, as are collaborations with other partners and institutions (for example, universities) to identify specific risks and to develop strategies that will address or mitigate potential impacts.

Scientific research

Northern Ellesmere Island has been of interest to the scientific community since the British Arctic Expedition, led by Captain George Nares from 1875–1876. Lieutenant Adolphus Greely established an American research base at Fort Conger for the first International Polar Year, 1882–1883, but it was during the first International Geophysical Year, 1957–1958, that the area became a veritable hub for science. The park’s present infrastructure makes it an invaluable asset to the operations of Natural Resources Canada’s Polar Continental Shelf Program, which supports services for all High Arctic research projects. Its proximity to the pole and relatively low impact from human activity make it an ideal place for climate change-related research and training. Findings are discussed at forums around the globe and recorded in professional publications.

Visitation and use

Visitation to Quttinirpaaq National Park is greatly affected by access since cruise ships and charter flights are the only ways to get to the park. Cruise ships can bring in upwards of 150 people for short visits, concentrated in a small area. Between 2008 and 2017, the average annual visitation on years when no cruise ship visited was 17 visitors. During this period, there were three years when ships did land, and the park saw an average of 215 visitors in those areas. In addition, an average of 20 researchers are in the park annually, spending anywhere from five days to two months, and while 40 to 150 Department of National Defence personnel may use the airstrip at Tanquary Fiord during the operating season, they rarely spend a night.

State of the park assessment

The Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada State of the Park Assessment (Parks Canada 2018) shows significant progress has been made to green park operations and decrease the overall footprint. All camps use solar energy as their primary source of electricity. Fuel management has been upgraded for greater environmental protection. A great deal of waste (metal, waste fuel, empty drums, old equipment) has been removed from the park. Tanquary Fiord Camp is the park’s primary operations base and, with its long airstrip and deep fiord, has evolved to serve as the central node for visitor activity. While currently under review, Parks Canada has been running a charter program since 2014 to facilitate visitor access and has built the supporting visitor accommodation at Tanquary Fiord. Parks Canada has also partnered with a tourism outfitter to provide parts of the program offer. The Ecological Integrity and Cultural Resource Monitoring Program – based on the Cultural Resource Inventory – are now established for the park and a first analysis of data was performed as part of the State of the Park Assessment (Parks Canada 2018). Two of the four cultural resource indicators show good results, one was fair, and the final indicator was not rated.

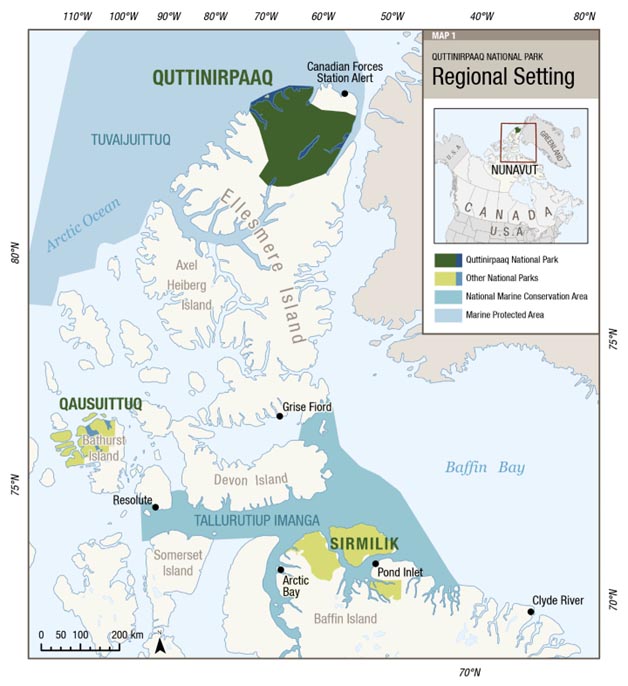

Map 1: Regional setting

Map 1: Regional setting — Text version

This map shows the regional setting of Quttinirpaaq National Park on northern Ellesmere Island.

The map contains a 0 to 200 kilometres scale in the bottom left, and a legend in the top right corner, which identifies the terrestrial and marine components of Quttinirpaaq National Park, other national parks, national marine conservation area, and marine protected area.

In particular, the map highlights the following other conservation sites in the region:

- Qausuittuq National Park (located on Bathurst Island)

- Sirmilik National Park (located on the northern end of Baffin Island)

- Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area (which includes the waters between Baffin Island and Devon Island in Lancaster Sound)

- Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area (which includes the marine waters off northern Ellesmere Island; it is not a site administered by Parks Canada)

The communities of Resolute (on Cornwallis Island) and Grise Fiord (on southern Ellesmere Island) are the two adjacent communities to Quttinirpaaq National Park, as defined by the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks.

Other Parks Canada protected sites in the area include Qausuittuq National Park on northern Bathurst Island, and Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area. Tuvaijuittuq, which includes the marine waters off northern Ellesmere Island, is the first Marine Protected Area to be designated for interim protection by ministerial order under the Oceans Act.

Map 2: Quttinirpaaq National Park

Map 2: Quttinirpaaq National Park — Text version

This is a map of Quttinirpaaq National Park. The general purpose of this map is to identify the park boundaries and important features, such as major ecological and cultural sites, the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Special Management Area, and the three operational camps located at Ward Hunt Island, Tanquary Fiord, and Lake Hazen.

Significant cultural resource sites at Kettle Lake and Fort Conger are depicted with a black circle. Black stars mark two Department of National Defence tower sites. Barbeau Peak – the highest mountain in Nunavut and the Canadian Arctic – is identified with a black cross.

The map contains a legend in the bottom right corner, and 0 to 20 kilometres scale in the bottom left corner.

Inuit used to live up here when they travelled only by dog team. Their sites are scattered all through here. Whether during dark season or only in the summer, it’s amazing they could do that. When you go up there and start learning about them, it makes you wonder, how did they do it? How did they survive? It baffles your mind. When you come up here, your mind wanders backwards to how it might have been. That’s what makes the park even more special.

4.0 Development of the management plan

During the development of the draft management plan, the Park Planning Team undertook early engagement exercises to discuss key vision elements, themes, and shared interests for Quttinirpaaq’s new management plan. This engagement consisted primarily of in-person meetings with key Inuit stakeholders in the communities of Resolute and Grise Fiord (for example, Hamlet councils, local Hunters and Trappers Associations, Elders, and business owners), and individual meetings with other government departments in-person or virtually. The Qikiqtani Inuit Association provided input and edits on the draft. The shared interests expressed in these edits and community engagement exercises were directly incorporated into the vision, key strategies, objectives, and targets of the draft management plan. In accordance with the Baffin IIBA, the Joint Park Management Committee approved the draft management plan in November 2019.

Between June and December 2022, the draft management plan was virtually mailed out and posted on an online engagement platform, where more than 850 users visited the English, French, and Inuktitut webpages about the project. Five written submissions were received. Open houses and small targeted stakeholder meetings occurred in the adjacent communities of Resolute (June-July 2022) and Grise Fiord (November 2022), and additional engagement with key stakeholders and other government departments continued virtually in winter 2023. Written materials were sent to stakeholders for comment if face-to-face meetings could not be arranged. No substantive issues were raised in consultations. In accordance with the Baffin IIBA, the Joint Park Management Committee approved the final draft plan in June 2023 for submission to the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, which then approved those parts of the draft plan that "concern the management and protection of particular wildlife or wildlife habitats"

(Baffin IIBA Article 5.3.35). All feedback on the draft plan informed the development of this final plan. A detailed overview of all comments that were received is included in a What We Heard report that is available on the Parks Canada webpage about Quttinirpaaq National Park.

5.0 Vision

Management of Quttinirpaaq National Park will be guided by these Inuit Societal Values:

Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq — Respect and care for the land.

Piliriqatigiinniq/Ikajuqtigiinniq — Working together for a common cause.

Tunnganarniq — Fostering good spirits by being open and welcoming.

Qanuqtuurniq — Being innovative and resourceful.

Pijitsirniq — Serving and providing for family and community.

Quttinirpaaq National Park is perched at the top of the world. Windswept and glacier carved, the years of change have traced their history across the expanse of northern Ellesmere Island and laid bare the history of geologic formation. Numerous cultural sites scattered throughout the expanse of the park bear testament to human ingenuity and adaptability, where people took advantage of natural routes and gentler climate provided by the landscape.

Quttinirpaaq holds value as a place uniquely situated to provide insight into the state of the Arctic and the changing global environment. Relatively undisturbed by current human activity, Quttinirpaaq’s unique and diverse ecosystems are healthy and remain connected to the greater systems surrounding it. Though signs of climate change are visible, life thrives here, and cultural resources are treasured and protected.

Mutual trust and respect are the foundations of building knowledge: Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and science are equally essential to our understanding and management of the park.

Quttinirpaaq National Park welcomes park visitors, Inuit, and other park users; meaningful experiences foster appreciation for the park as well as the Eastern High Arctic Region. The park’s infrastructure and assets will adequately serve all park user needs and reflect a thoughtful, low-impact approach that considers future change. Parks Canada has strong relationships to support the achievement of its mandate and its commitments to cooperatively manage the park with Inuit. Strong connections between the park, local communities, Nunavummiut, and national and international audiences foster appreciation and understanding of Quttinirpaaq and the greater region. Innovation and resourcefulness guide Parks Canada’s success in fulfilling all aspects of its mandate and commitments.

My first year working there I fell in love with the place right away and kept going back. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful as those mountains and valleys, with all the wildlife.

I will forever love this place. It’s a big part in my heart for that place.

6.0 Key strategies

In this section

- Key strategy 1: Honouring shared commitments

- Key strategy 2: Working together

- Key strategy 3: Learning from people and land

Three key strategies describe the integrated approach to the management of Quttinirpaaq National Park for the next ten years. These strategies are based on priorities determined by the Park Planning Team, the Joint Park Management Committee, and Parks Canada, and are consistent with Canada’s Arctic Policy Framework (released September 10, 2019). Meeting the objectives and targets of each strategy will direct how human and financial resources are allocated to realize our shared vision. Many of the targets are cross-cutting and serve more than one objective. Where applicable, references to relevant Articles in the Baffin IIBA have been included to demonstrate the direct link between management plan commitments and IIBA implementation.

Target dates are relative to the date of signing the plan, and unless otherwise specified, targets are to be met within the ten-year life of the plan or are ongoing commitments.

Key strategy 1

Honouring shared commitments

Core objectives of the Nunavut Agreement are to encourage self-reliance and the cultural and social well-being of Inuit. The Baffin IIBA is a tool used to honour Inuit rights and provide opportunities for Inuit to benefit from the establishment, planning, management, and operation of the park, particularly in the adjacent communities. Indeed, Parks Canada works to be an active member of Resolute and Grise Fiord, and to collaborate with other federal departments to provide capacity-building opportunities for Inuit participation in park management, economic, and employment roles. Guided by the Inuit Societal Value of Pijitsirniq (serving and providing for family and community), this strategy outlines objectives and targets through which Parks Canada will honour its obligations in the Nunavut Agreement and the Baffin IIBA to provide benefits to Inuit related to Quttinirpaaq National Park.

Objective 1.1

Inuit continue to be actively involved in the management of Quttinirpaaq National Park.

Targets

- An orientation for new and returning Joint Park Management Committee members is developed and implemented within the first two years. Parks Canada will reach out to the Qikiqtani Inuit Association to invite them to co-develop this product (Baffin IIBA Article 5.1.29)

- At least one Inuit Knowledge Working Group project will be initiated within seven years (Baffin IIBA Objective [e])

- Park management will actively promote and facilitate Inuit-led research projects from adjacent communities within two years (Baffin IIBA Article 6.1.16)

Objective 1.2

Opportunities for greater Inuit involvement in employment and increased economic benefits are realized in the adjacent communities.

Targets

- At least one position associated with Quttinirpaaq extending beyond the operational season will be located in Resolute or Grise Fiord (Baffin IIBA Article 9.1.1)

- Inuit staff from Resolute and Grise Fiord are mentored and provided training to achieve their career goals (Baffin IIBA Article 9.2.1)

- The Baffin IIBA Economic Opportunities Fund held by Kakivak is promoted in the adjacent communities and Inuit are supported to develop opportunities and applications for that and other funding (Baffin IIBA Article 10.3.2)

- Parks Canada will contribute to at least one regional skills development and capacity-building initiative in Resolute or Grise Fiord every two years, e.g., tourism, research (Baffin IIBA Article 9.2.4)

Objective 1.3

Park management, planning, and operations will provide opportunities for Inuit from Resolute and Grise Fiord to develop stronger connections to the park.

Targets

- Within three years, create at least two learning activities that could be led by a community member to communicate knowledge and stimulate interest in the park to the communities of Resolute and Grise Fiord

- The Joint Park Management Committee will at minimum hold two meetings in the park during the life of this management plan

- At least two non-Joint Park Management Committee community members from each adjacent community visit the park once every three years through Parks Canada programming

- An Inuk Youth Representative position (non-voting) on the Joint Park Management Committee is established within one year and maintained for the life of the plan

- Complete an Inuktitut Place Names project. These names will be used and promoted by Parks Canada through our maps and materials

- Facilitate the sharing of research through a community event and other means (e.g., social media, radio, newsletter, schools)

- Parks staff will facilitate connections between researchers and communities

Key strategy 2

Working together

Quttinirpaaq National Park supports several different user groups: it is traditional home and hunting ground for Inuit, a hub for northern research, a staging point for military operations, and a place for adventuring. Its remoteness, however, means access is a financial and logistical challenge for everyone, which makes working together on shared goals essential. For Parks Canada, major challenges include the upkeep of infrastructure that is key to program implementation, delivery of visitor opportunities, and enhancing our understanding of the park’s natural and cultural heritage. Additionally, conservation is more successful when aligned with regional initiatives for activities inside and outside the park. Quttinirpaaq management will be guided by the Inuit Societal Value of Qanuqtuurniq (being innovative and resourceful) to proactively seek out ways to work with others to ensure continued success. Effective multilateral communication and relationship building with communities and key partners is essential to realize this success.

Objective 2.1

Quttinirpaaq has the appropriate level of safe, well-maintained infrastructure to support current and expected partners and users.

Targets

- Within five years, needs of visitors, stakeholders, partners, researchers, and park operations will be considered in the development of an asset strategy to guide all future asset management

- User groups relying on the infrastructure in Quttinirpaaq support maintenance and operation of that infrastructure

- Formal agreements are in place for in-park facilities and their use

Objective 2.2

The relationship between Parks Canada and the tourism industry is strengthened to foster meaningful tourism initiatives in the region.

Targets

- Promotional material for Quttinirpaaq is available for Resolute and Grise Fiord businesses within one year

- Opportunities to promote tourism through non-government agencies and organizations with a mandate and interest in conservation, tourism, outdoor education, culture, and nature are pursued

- Continue working with commercial tourism operators to bring a sustainable number of visitors to the park

- Make connections between community members interested in tourism to the opportunities and support available for developing their skills and businesses

Objective 2.3

Innovative approaches to address park management issues are fostered through collaboration, multilateral communication, and relationship building with partners and stakeholders.

Targets

- Collaborate with stakeholders to implement Species at Risk Act strategies and actions, specifically with regard to Peary caribou and Porsild’s Bryum

- Collaborate with the management of Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area, Qausuittuq National Park, and Polar Continental Shelf Program to maximize resource efficiency

- Seek opportunities to support the re-establishment of historical human ties to Greenland

- Finalize Memorandum of Understanding with Polar Continental Shelf Program within one year and Department of National Defence within three years, to guide our continued relations

- Work with Tuvaijuittuq (High Arctic Basin) and regional conservation initiatives as appropriate

Objective 2.4

Through collaboration with researchers and consultation with communities, the research in Quttinirpaaq meets scientific priorities, community interests, and strengthens Inuit participation in research.

Targets

- Continue to host scientific research of national and global importance and encourage researchers to make data publicly available

- Research priorities are reviewed and updated with Joint Park Management Committee every five years

- There is research conducted in the park that reflects shared Parks Canada, Joint Park Management Committee, and community interests

- At least one Inuk researcher initiates a research project in the park and is supported by Parks Canada (Baffin IIBA Article 6.1.16)

- Encourage research projects that bring together Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and Science

Key strategy 3

Learning from people and land

This strategy underlines the opportunity Quttinirpaaq provides to learn from the unique coexistence Inuit share with land and wildlife. It is a place where we can study the effects of geologic forces and change in rocks, ice, and ecosystems over millions of years. Quttinirpaaq offers the opportunity to understand Arctic ecosystems and climate change in an environment situated close to the North Pole and used but relatively unchanged by human activity. Quttinirpaaq management will bring together science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit to foster Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq (respect and care for the environment) and increase our understanding of the natural and cultural resources of the park and the greater region. This knowledge will be used to encourage global appreciation and understanding of the High Arctic, the impacts of climate change, and humanity’s ingenuity and ability to adapt to challenges and changing circumstances.

Objective 3.1

Public outreach tools and programs include Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and effectively communicate the values of Quttinirpaaq to all Canadians and beyond.

Targets

- One outreach activity showcasing a story based on an understanding of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and science of Quttinirpaaq is available for staff to share and present within two years, with a priority on youth audiences where possible

- Research and monitoring activities in the park are showcased on the Quttinirpaaq website and communicated to the communities annually

- Provide the Cultural Resource Inventory to the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, Inuit Heritage Trust, and Government of Nunavut

- Opportunities to access Quttinirpaaq’s cultural resources virtually are increased and enhanced

- Efforts are made to advance preparation of a nomination for inscription on the list of World Heritage Sites upon the advice and recommendations of management partners

- Opportunities to share research stories in innovative and collaborative ways with partners will be explored

Objective 3.2

Research and ongoing monitoring programs in Quttinirpaaq National Park improve our knowledge and understanding of the park and Arctic ecosystems.

Targets

- Ecological Integrity and Cultural Resource monitoring programs provide usable data for making management decisions

- Within two years, a climate change vulnerability assessment of targeted park assets will have provided the necessary results to inform an asset strategy

- A protocol to monitor the impact of climate change on targeted cultural resources will be implemented within five years

- At least one ecological integrity indicator will be developed based on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Objective 3.3

User needs and the principles of environmental sustainability are met with appropriate infrastructure and improved learning opportunities.

Targets

- Quttinirpaaq’s capacity with respect to visitor and park user numbers in a given year will be determined within five years

- A strategy to monitor, assess, and communicate the safety of major hiking routes in the park will be implemented within the first three years of this management plan

- Park visitor information and interpretive materials will be assessed, and an updated implementation plan will be created within two years of signing this plan

- Visitors to Fort Conger in the company of park staff have accurate information on the history of the site within two years

- Within five years, cruise ship guide training and site guidelines for Fort Conger ensure the safety of both visitors and the resources during cruise ship visits that are unaccompanied by park staff

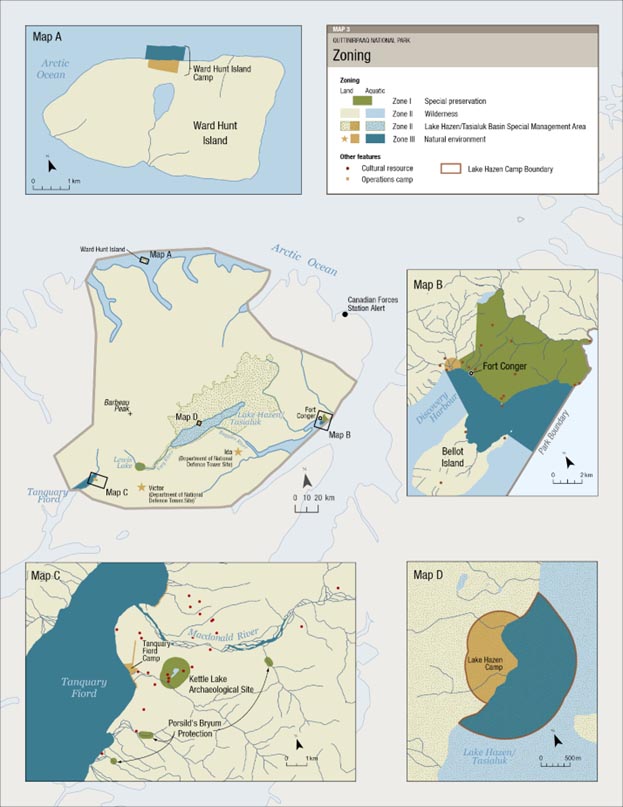

7.0 Zoning

Parks Canada’s national park zoning system is an integrated approach to the classification of land and water areas in a national park and designates where particular activities can occur on land or water based on the ability to support those uses. The zoning system has five categories:

- Zone I – Special Preservation

- Zone II – Wilderness

- Zone III – Natural Environment

- Zone IV – Outdoor Recreation

- Zone V – Park Services

Three zones are used in Quttinirpaaq National Park: Zones I, II, and III (see Map 3). This zoning plan is consistent with Section 8.2.8 of the Nunavut Agreement, which states that "each National Park in the Nunavut Settlement Area shall contain a predominant proportion of Zone I – Special Preservation and Zone II – Wilderness."

Zoning provisions do not apply to Inuit exercising traditional harvesting rights within Quttinirpaaq National Park (Nunavut Agreement, Article 5.7.16).

The major change in zoning from the 2009 management plan is the approach to the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin, which has shifted to Zone II with a Special Management Area designation, as describe in section 7.0 and Map 4.

Several Zone I sites have been added to conserve Porsild’s Bryum, a species listed on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act as "Threatened"

in 2011 (Map 3c). Adjustments have also been made to the Zone III areas around airstrips and camps to accommodate current and projected use patterns.

Otherwise, zoning remains relatively unchanged from the previous management plan. The prohibition on sport fishing in Quttinirpaaq National Park, approved by the NWMB in 2006, remains in effect.

Zone I: Special Preservation

Zone I provides strong protection to several of the unique natural and cultural features of Quttinirpaaq National Park. Preservation is the key consideration, and visitor access may be prohibited or controlled. Motorized use within these sites is not allowed, except for exceptional circumstances as permitted by the superintendent and upon the advice of the Joint Park Management Committee. Camping within the boundaries of a Zone I is not permitted.

There are six Zone I areas: Kettle Lake, Fort Conger, Lewis Lake, and three sites for the protection of Porsild’s Bryum.

Kettle Lake

The suite of cultural resources around Kettle Lake is representative of the High Arctic and includes features from both the Thule and Independence I cultures. In addition to the large, visible features such as fox traps, tent rings, caches and hunting blinds, numerous smaller artifacts remain in situ, though some have been removed for conservation. Because of its proximity to the Tanquary Fiord base camp, it is an excellent opportunity for visitors to experience ancient and recent arctic history in the company of Parks Canada staff or a Parks Canada trained guide. While less preferred, independent day-use visitation is permitted with the support of a self-guided brochure, following orientation from park staff. Kettle Lake resources are monitored regularly.

Fort Conger

The buildings and historical artifacts at Discovery Harbour are known collectively as Fort Conger; together, they are the combined remains of American and European High Arctic Exploration base camps established by George Nares, Adolphus Greely, and Robert Peary between 1875 and 1909. Greely’s 1881–1883 scientific studies were part of the First International Polar Year (a designated event of national historical significance), and the Peary Huts are designated “classified” by the Federal Heritage Building Review Office. The site is also uniquely situated to demonstrate the contributions Inuit made to the success of Arctic explorers. Contamination is a concern at the site, and appropriate signage has been installed. While the features themselves are considered vulnerable and at risk due to climate change, the obstacles and limitations are such that a relatively low level of human visitation is expected and does not need to be prevented. A target of this plan is to develop a strategy for sharing this site through Parks Canada trained guides. Until that time, visitors must be accompanied by Parks Canada employees. Toddlers and infants, who are more susceptible to the contaminants, are not allowed to visit the site.

Lewis Lake

Arctic wolves have been denning in the vicinity of Lewis Lake for what appears to be several thousand years. The den site here is integral to the seasonal cycle of wolf populations, and there is a history of past disturbance to the pack. The lake lies along the major long-distance hiking route in the park. A Zone I designation provides a three-kilometre buffer surrounding the lake and den. Non-motorized access is permitted but camping is not. All visitors will be informed of the importance of not disturbing the wolves.

Porsild’s Bryum Protection

Porsild’s Bryum is a small, rare cushion moss growing in a limited number of colonies globally. It favours moist, shady locations at higher elevations. Listed as threatened by the Species at Risk Act, there are three known populations in Nunavut, and they are all in the Tanquary Fiord area of Quttinirpaaq National Park. These three pockets are considered critical habitat and classified Zone I for their protection. While access is permitted in these areas, the visitor orientation stresses the importance of walking on hard surfaces and not stopping to linger, as the moss could be inadvertently damaged. The National Recovery Strategy to monitor known populations will be implemented and surveys for additional populations will take place during the lifespan of this plan, subject to funding. If found, appropriate protective management actions will be taken on advice from species experts and the Joint Park Management Committee.

Zone II: Wilderness

These extensive Zone II areas provide visitors with the opportunity to experience relatively undisturbed representations of a natural High Arctic region and will be conserved in a wilderness state. The perpetuation of ecosystems with minimal human interference is the key consideration. Suggested routes are unmarked and unmaintained, and still require a level of skill to find one’s way. Motorized use by visitors is not permitted except for strictly controlled air access in remote areas.

The majority of the park is Zone II. Indeed, all areas of the park not otherwise identified as Zone I or Zone III shall be considered a Zone II designation.

Limited access by aircraft may be permitted on a case-by-case basis. Winter/spring access to Mount Barbeau and other glaciated areas was identified as an adventure ski opportunity which would be greatly simplified by air access. Due to seasonal changes, however, a specific landing location cannot be identified; these requests will be considered individually.

Zone III: Natural Environment

Zone III areas provide opportunity for low-impact visitor experiences through outdoor recreation activities requiring minimal services and facilities of a rustic nature. While motorized access may be allowed, it will be controlled. These are the areas of the park with the greatest levels of access and activity.

Most of the park’s infrastructure and major access points have been designated Zone III. The size of these zones has been modified somewhat from the previous plan to fit more closely with current use patterns and to simplify permitting. Controlled motorized use is permitted in these areas, but users, except for park operations, require a permit.

In total, there are six Zone III sites in the park. Three of these areas are current Parks Canada operational sites, which includes Ward Hunt Island Camp, Tanquary Fiord Base of Operations, and Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Camp (see the Map 3 insets). For all three sites, Zone III encompasses the buildings and airstrips.

Ward Hunt Island (Map 3a)

Although under long-term administration by Parks Canada, Ward Hunt Island was officially added to the land description of Quttinirpaaq National Park under the Canada National Parks Act in October 2023.

Tanquary Fiord Base of Operations (Map 3c)

The fiord itself, the shoreline around camp, and a small strip of shoreline north of the MacDonald River outflow is also Zone III to allow for small vessel landings. Private yacht access is permitted.

Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Camp (Map 3d)

The Zone III area was extended to allow planes to land on the lake when ice-covered, as this is a safer option in the spring. An additional Zone III extension over land is solely for the purpose of boring for materials to repair the airstrips, which should happen at a distance from the lake that prohibits runoff (see also Map 4 and Section 7.0 regarding the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Management Area).

A newly designated Zone III area includes the northern entrance to Discovery Harbour, and the shoreline of a small bay and unmaintained airstrip immediately west of Fort Conger (Map 3b). This change to Zone III allows for simplified permitting of aircraft landings, while also authorizing cruise ship zodiac landings on the beach.

Finally, two Department of National Defence (DND) microwave towers and stations are designated Zone III sites in order to facilitate DND access via helicopter, which is required frequently during the summer season for maintenance. Visitor access is not permitted (see Map 3).

Map 3: Quttinirpaaq National Park Zoning

Map 3: Quttinirpaaq National Park Zoning — Text version

This map shows the zoning plan for Quttinirpaaq National Park. In accordance with the Nunavut Agreement, the predominant zone of the park is Zone II – Wilderness. Four inset maps highlight zoning at specific areas in the park: Ward Hunt Island (Map 3a), Fort Conger (Map 3b), Tanquary Fiord Operations Camp (Map 3c), and Lake Hazen Operations Camp (Map 3d).

The main zoning map contains a 0 to 20 kilometres scale. Each inset map has its own scale, ranging from 0 to 500 metres (Map 3d), 0 to 1 kilometre (Map 3a and 3c), and 0 to 2 kilometres (Map 3b).

Zoning provisions do not apply to Inuit exercising traditional harvesting rights within Quttinirpaaq National Park (Nunavut Agreement, Art. 5.7.16).

8.0 Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Management Area

Lake Hazen, or Tasialuk as it is known to many Inuit, is the deepest lake north of the Arctic Circle. The unique conditions of the lake’s drainage basin, with a mountain range to the north and a plateau to the south, create a microclimate that is warmer and thus more fertile than the surrounding polar desert. As a result, the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin (Map 4) is considered a polar oasis, with meadows of lush grasses and marshes of flowers a stark contrast to the largely unproductive landscape found elsewhere in the High Arctic.

The Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin is nestled in a natural corridor between mountain and glacier along the route known as the Muskox Way, a migration corridor for Independence I people across northern Ellesmere to Greenland. The density of recorded archaeological sites in this area demonstrates its importance to multiple groups of people spanning over 4,000 years, from Paleo-Inuit, to Thule, and to Greenlandic Inughuit cultures more recently. The biodiversity of the entire region has provided food and shelter for those who passed through, those who stayed, and those who came simply to harvest resources. The area has also been the subject of important scientific research documenting its sensitivity to climate change and the unprecedented changes to hydrology, nutrients, temperature, algae growth, ice cover and fish conditions over the past 300 years. For these reasons, the entire Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin was initially designated Zone I in the first management plan.

Shifting from Zone I to Zone II and taking an area management approach highlights the importance of maintaining a high level of protection for this very special naturally and culturally sensitive region, while encouraging continued research and small-scale visitation in a way that is consistent with Parks Canada zoning in other locations. For example, although visitation in the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin has been low in the past few years, there are numerous hiking opportunities in the area, including a part of the Muskox Way. This change offers a chance to specifically consider the unique opportunities and challenges of this special place.

As discussed in the section above, the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Camp is a small Zone III designation within the larger management area. The following objectives have been defined to address the management issues in the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin.

Objective 1

Use Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and science to ensure human use does not negatively affect the ecological values of the area.

- An environmental code of conduct, developed with the Joint Park Management Committee, will guide use of the area, and be recommended for Inuit users as well

- Knowledge gaps around ecological integrity are identified

- Seek funding or partnerships for active management or monitoring as identified in the knowledge gap analysis

- Rezoning to Zone I for sites where evidence justifies

- Analysis of operations at Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Camp ensures all activity is aligned with the long-term goal of ensuring the ecological integrity and protection of Lake Hazen/Tasialuk in light of the continued changes expected due to climate change

Objective 2

To ensure that human use does not negatively affect cultural resources.

- All users of the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin are provided detailed information regarding appropriate behaviour around archaeological sites and asked to report specific locations of any feature found

- Camping areas will be identified and promoted along the Very River in locations where there are no cultural resources

- Promote known hiking routes away from identified archaeological sites

- Culturally sensitive areas are considered when reviewing research and special activity requests

- Confirm locations of cultural resources as opportunities allow

- Rezone specific areas to Zone I if assessment justifies this action

Map 4: Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Special Management Area

Map 4: Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Basin Special Management Area — Text version

This map shows the Lake Hazen/Tasialuk Management Area. The area is Zone II, with the exception of the Zone III Lake Hazen Operations Camp, and the Zone I area around Lewis Lake to protect denning Arctic wolves. Cultural resource sites within the special management area are highlighted in red. The map contains a legend in the top left corner, and 0 to 10 kilometres scale in the bottom right corner.

9.0 Summary of strategic environmental assessment

All national park management plans are assessed through a strategic environmental assessment to understand the potential for cumulative effects. This understanding contributes to evidence-based decision-making that supports ecological integrity being maintained or restored over the life of the plan. The strategic environmental assessment for the management plan for Quttinirpaaq National Park considered the potential impacts of climate change, local and regional activities around the park, and proposals within the management plan. The strategic environmental assessment assessed the potential impacts on different aspects of the ecosystem, including the tundra (vegetation, active layer, Peary caribou, polar bear, Porsild’s Bryum) and freshwater (water quality, Arctic char).

Value components were found to not be significantly at risk from cumulative effects, as the primary stressor to the park’s natural environment is the changing global environment. The management plan includes approaches to understand impacts to these valued components including:

- connecting with partners, stakeholders, and Inuit from the park’s adjacent communities to promote and strengthen regional collaboration related to understanding impacts of the changing global environment on the park’s natural systems

- Continuing the active involvement of Inuit in the management and operations of Quttinirpaaq

Indigenous partners, stakeholders and the public were provided with opportunities to provide comments on the draft plan, and a draft of this strategic environmental assessment. Comments from the public, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders were incorporated into the strategic environmental assessment and management plan as appropriate.

The SEA was conducted in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals (2010) and facilitated an evaluation of how the management plan contributed to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. Individual projects undertaken to implement management plan objectives at the site will be evaluated to determine if an impact assessment is required under the Impact Assessment Act or successor legislation. The management plan supports the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goals of Greening Government, Healthy Coasts and Oceans, Sustainably Managed Lands and Forests, Healthy Wildlife Populations, Connecting Canadians with Nature, and Safe and Healthy Communities.

There are no important negative environmental effects anticipated from implementation of the Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Management Plan.

For more information about the management plan or about Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada: Quttinirpaaq National Park of Canada Phone: 867-975-4673 (Iqaluit office) © His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the President & Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2023. Front cover image credit: Cette publication est aussi disponible en français : ᐅᓇ ᐊᒥᓱᓕᐅᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂ ᓴᖅᑭᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᒻᒥᔪᖅᑕᐅᖅ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑑᖓᓪᓗᓂ.

Contact us

P.O. Box 278

Iqaluit NU X0A 0H0

CanadaPublication information

top from left to right: Parks Canada

bottom: Parks Canada

Plan directeur du parc national du Canada Quttinirpaaq, 2023

- Date modified :